Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference

Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference 中国人民政治协商会议 | |

|---|---|

| 14th National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| History | |

| Founded | 21 September 1949 |

| Preceded by | National Assembly |

| Leadership | |

See list

| |

Main Organ | Plenary Session & Standing Committee of National Committee, CPPCC Plenum of the CPPCC (Historical) |

| Structure | |

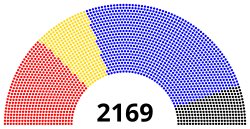

| Seats | NC-CPPCC: 2169 NC-CPPCC Standing Committee: 324 |

| |

NC-CPPCC political groups | CCP, minor parties, and independents (544) People's organizations (313) |

| |

NC-CPPCC Standing Committee political groups | CCP, minor parties, and independents (193) People's organizations (30) |

Length of term | 5 years |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Great Hall of the People, Xicheng District, Beijing City, People's Republic of China | |

| Website | |

| en | |

| Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 中国人民政治协商会议 | ||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國人民政治協商會議 | ||||||

| |||||||

| Short form | |||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 人民政协 | ||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 人民政協 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | People's Political Consultation | ||||||

| |||||||

| Shortest form | |||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 政协 | ||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 政協 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | Political Consultation | ||||||

| |||||||

| Third alternative Chinese name | |||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 新政协 | ||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 新政協 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | New Political Consultation | ||||||

| |||||||

|

|---|

|

|

The Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) is a political advisory body in the People's Republic of China and a central part of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)'s united front system. Its members advise and put proposals for political and social issues to government bodies.[1] However, the CPPCC is a body without real legislative power.[2] While consultation does take place, it is supervised and directed by the CCP.[2]

The body traditionally consists of delegates from the CCP and its people's organizations, eight legally permitted political parties subservient to the CCP, as well as nominally independent members.[3][4][5] The CPPCC is chaired by a member of the Politburo Standing Committee of the CCP. In keeping with the united front strategy, prominent non-CCP members have been included among the Vice Chairs, examples being Chen Shutong, Li Jishen and Soong Ching-ling.[6]

The organizational hierarchy of the CPPCC consists of a National Committee and regional committees. Regional committees extend to the provincial, prefecture, and county level. According to the charter of the CPPCC, the relationship between the National Committee and the regional committees is one of guidance and not direct leadership. However, an indirect leadership exists via the United Front Work Department at each level.[7][8] The National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference typically holds a yearly meeting at the same time as plenary sessions of the National People's Congress (NPC). The CPPCC National Committee and NPC plenary sessions are collectively called the Quanguo Lianghui ("National Two Sessions").

The CPPCC is intended to be more representative of a broader range of people than is typical of government office in the People's Republic of China, including a broad range of people from both inside and outside the CCP. The composition of the members of the CPPCC changes over time according to national strategic priorities.[9] Previously dominated by senior figures in real-estate, state-owned enterprises, and "princelings", the CPPCC in 2018 was primarily composed of individuals from China's technology sector.[10]

History

[edit]

The origins of the conference date prior to the existence of the People's Republic of China. During negotiations between the Chinese Communist Party and the Kuomintang in 1945, the two parties agreed to open multiparty talks on post-World War II political reforms via a Political Consultative Conference. This was included in the Double Tenth Agreement. This agreement was implemented by the National Government of the Republic of China, who organized the first Political Consultative Assembly from 10 to 31 January 1946. Representatives of the Kuomintang, CCP, Chinese Youth Party, and China Democratic League, as well as independent delegates, attended the conference in Chongqing.[citation needed]

After major successes in the civil war, the CCP, on 1 May 1948, invited the other political parties, popular organizations and community leaders to form a new Political Consultative Conference to discuss a new state and new coalition government.[11]

In 1949, with the CCP having gained control of most of mainland China, they organized a "new" Political Consultative Conference in September, inviting delegates from various friendly parties to attend and discuss the establishment of a new state.[2] This conference was then renamed the People's Political Consultative Conference. On 29 September 1949, the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference unanimously adopted the Common Program as the basic political program for the country.[12]: 25 The conference approved the new national anthem, flag, capital city, and state name, and elected the first government of the People's Republic of China.[2]

From 1949 to 1954, the conference became the de facto legislature of the PRC. During this period, it issued nearly 3,500 laws, laying the foundations of the newly established PRC. In 1954, the Constitution transferred legislative functions to the National People's Congress.[13]

During the Hundred Flowers Campaign between 1956 and 1957, Mao Zedong encouraged members of the CPPCC to speak about the shortcomings of the CCP. However, those who did faced severe repercussions such as heavy criticism and or incarceration in labor camps in the subsequent Anti-Rightist Campaign.[2]

Along with most other institutions, the CPPCC was effectively decimated during the Cultural Revolution.[13] It was revived during the First Session of its 5th National Committee between 24 February to 8 March 1974, during which Deng Xiaoping was elected as its chairman.[2] New rules for the CPPCC were issued in 1983, which limited the proportion of CCP members to 40 percent.[13]

Since the beginning of economic reforms, the CPPCC increasingly focused on accommodating Hong Kong and Macau elites and attracting investment from overseas Chinese communities.[13] A new "Economy Sector" was created inside the CPPCC in 1993, and the 1990s saw an increase in the number of business-oriented CPPCC members, many of whom saw the CPPCC as a way to network and communicate with officials in the party-state apparatus.[13]

When plans for the Sanxia (Three Gorges) Dam were revived by the CCP during the emphasis on the Four Modernizations during the early period of Reform and Opening Up, the CPPCC became a center of opposition to the project.[14]: 204 It convened panels of experts who recommended delaying the project.[14]: 204

Present role

[edit]The CPPCC is the highest-ranking body in the united front system.[7] It is the "peak united front forum, bringing together CCP officials and Chinese elites."[15] According to Sinologist Peter Mattis, the CPPCC is "the one place where all the relevant actors inside and outside the party come together: party elders, intelligence officers, diplomats, propagandists, soldiers and political commissars, united front workers, academics, and businesspeople."[16] In practice, the CPPCC serves as "the place where messages are developed and distributed among party members and the non-party faithful who shape perceptions of the CCP and China."[16]

The CPPCC includes deputies elected from the CCP and its people's organizations, the eight legally permitted political parties subservient to the CCP, as well as nominally independent deputies[17] The party's Organization Department is responsible for the nomination of prospective deputies who are CCP members.[18]: 61

The CPPCC provides a deputy "seat" for the 8 non-communist parties and so-called "patriotic democrats".[17] The CPPCC also reserves seats for overseas delegates,[19] as well as regional deputies from Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan.[1] Non-communist party members of the CPPCC are nominated by the party's United Front Work Department for appointment or election to the Conference.[18]: 61

The conception of the non-communist parties as part of a coalition rather than an opposition is expressed in the PRC's constitutional principle of "political consultation and multiparty cooperation."[17] In principle, the CCP is obliged to consult the others on all major policy issues.[17] In the early 2000s, CPPCC deputies frequently petitioned the CCP Central Committee regarding socioeconomic, health, and environmental issues.[17]

"The Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, a broadly based representative organization of the united front which has played a significant historical role, will play a still more important role in the country’s political and social life, in promoting friendship with other countries and in the struggle for socialist modernization and for the reunification and unity of the country. The system of the multi-party cooperation and political consultation led by the Communist Party of China will exist and develop for a long time to come."

According to state media Xinhua News Agency, the CPPCC is described as an "organization in the patriotic united front of the Chinese people." It is further explained that the CPPCC is neither a body of state power nor a policy-making organ, but rather a platform for "various political parties, people's organizations, and people of all ethnic groups and from all sectors of society" to participate in state affairs.[21]

As a united front organ, the CPPCC collaborates with the CCP's United Front Work Department. According to Mattis, the CPPCC gathers the society's elite, while the UFWD "implements policy and handles the nuts and bolts of united front work." The UFWD oversees the people's organizations' deputies, who constitute the membership of the CPPCC, and manages any nomination work for potential deputies to be elected to the Conference from these organizations.[16]

National Committee

[edit]

The National Committee of CPPCC (中国人民政治协商会议全国委员会, shortened 全国政协; 'National PCC') is the national-level organization that represents the CPPCC nationally and is composed of deputies from various sectors of society. Deputies of the National Committee are elected for five-year terms, though this can be extended in exceptional circumstances by a two-thirds majority vote of all deputies of the Standing Committee.[22]

The National Committee holds plenary sessions annually, though a session can be called by the National Committee's Standing Committee if necessary.[22] The plenary sessions are generally held in March, around the same date as the annual session of the National People's Congress; together, these meetings are termed as the Two Sessions.[23] During the Two Sessions, the CPPCC and the NPC hear and discuss reports from the premier, the prosecutor general, and the chief justice.[18]: 61–62 Every CPPCC plenary session makes amendments to the CPPCC charter, elects on every first plenary session the Standing Committee, which handles the regular affairs of the body, and adopts resolutions on the National Committee's "major working principles and tasks".[22] The Standing Committee is responsible for selecting deputies to the Conference, implementing the CPPCC's resolutions, and interpreting its official charter.[22]

The National Committee is led by a chairman, currently Wang Huning, one of the highest-ranking offices in the country; since its establishment, all CPPCC chairpersons have been a member of the Politburo Standing Committee of the CCP except during transition periods, being at least its 4th-ranking member.[16][15] The chairman is assisted by several vice chairpersons and a secretary-general, who heads the National Committee's General Office; together, they make up the Chairperson's Council, which handles the day-to-day affairs of the Standing Committee and convences its sessions on an average of at least one committee session per month, unlike the SC-NPC which holds its sessions bimonthy.[16][22] Council meetings coordinate work reports sent to the Standing Committee and the wider National Committee, review united front work, identify the issues to focus on during SC-NCCPPCC sessions and the annual general plenary, and highlight important ideological directions of the CCP.[16] It also presides over the preparatory meeting of the first plenary session of the next National Committee.[22]

The CCP and the aligned minor parties are assigned deputies in the National Committee. Besides political parties, the NC-CPPCC has also deputies from various sectors of society in its ranks.[24] Members include scientists, academics, writers, artists, retired government officials, and entrepreneurs, among other sectors.[18]: 61 The parties and groups with elected deputies to the NC-CPPCC are as follows:[25]

Standing Committee of the National Committee

[edit]The Standing Committee of the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference performs the duties of the CPPCC in between plenary sessions of the National Committee. It is responsible for all actions taken by the whole of the National Committee of the Conference or by individual deputies of it. According to the bylaw, the Chairman of the National Committee is Chairman of the Standing Committee ex officio.[26][27][28]

Special Committees of the National Committee

[edit]The National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference contains several Special Committees, which are headed by the Standing Committee. The Special Committees typically have around sixty individual members, including a chairperson and ten or more vice-chairs. Like the main Conference, the Special Committees include a wide range of deputies from the relevant sectors forming its membership.[16] The CPPCC National Committee currently has 10 Special Committees organized similarly to that of the Standing Committee:[25]

- Committee for Handling Proposals

- Committee for Economic Affairs

- Committee for Agriculture and Rural Affairs

- Committee of Population, Resources and Environment

- Committee of Education, Science, Culture, Health and Sports

- Committee for Social and Legal Affairs

- Committee for Ethnic and Religious Affairs

- Committee for Liaison with Hong Kong, Macao, Taiwan and Overseas Chinese

- Committee of Foreign Affairs

- Committee on Culture, Historical Data and Studies

Publication

[edit]The People’s Political Consultative Daily (人民政协报) is the official newspaper of the National Committee of the CPPCC.[29]

Regional committees

[edit]In addition to the main National Committee, the CPPCC contains numerous regional committees at the provincial, prefecture, and county level.[22] According to an old post in CPPCC's website, there were 3,164 local CPPCC committees at every level by the end of 2006, containing around 615,164 deputies elected in like manner as the National Committee.[16] Like the National Committee, the regional committees serve for five year terms, have a chairperson, vice chairpersons and a secretary-general, convene plenary sessions at least once a year, and have a standing committee with similar functions.[22] According to the CPPCC charter, the relationship between the National Committee and the local committees, as well as the relationship between the local committee and lower-level committees is "one of guidance".[30]

The following regional committees are modeled after the National Committee with identical composition of deputies elected to them and are each supervised by regional level Standing Committees:[2][22]

- CPPCC province-level committees

- including regional committees of the autonomous regions and city committees of directly controlled municipal governments (Beijing, Tianjin, Chongqing and Shanghai)

- CPPCC prefecture-level committees

- including autonomous prefectural committees and city committees of sub-provincial and prefectural cities

- CPPCC county-level committees

- including committees of autonomous counties and country-level cities

See also

[edit]- Chinese Literature and History Press, the CPPCC's publishing house

- List of current members of CPPCC by sector

References

[edit]- ^ a b Tiezzi, Shannon (4 March 2021). "What Is the CPPCC Anyway?". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 28 March 2024. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g Colin Mackerras; Donald Hugh McMillen; Andrew Watson (2001). Dictionary of the Politics of the People's Republic of China. London: Routledge. p. 70. ISBN 0-203-45072-8. OCLC 57241932.

- ^ Pauw, Alan Donald (1981). "Chinese Democratic Parties as a Mass Organization". Asian Affairs. 8 (6): 372–390. doi:10.1080/00927678.1981.10553834. ISSN 0092-7678. JSTOR 30171852.

- ^ Rees-Bloor, Natasha (15 March 2016). "China's largest political conference – in pictures". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ "The United Front in Communist China" (PDF). Central Intelligence Agency. May 1957. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 January 2017. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- ^ Shih, Wen (1 March 1963). "Political Parties in Communist China". Asian Survey. 3 (3): 157–164. doi:10.2307/3023623. ISSN 0004-4687. JSTOR 3023623.

- ^ a b Bowe, Alexander (24 August 2018). "China's Overseas United Front Work: Background and Implications for the United States" (PDF). United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 September 2018. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ Dotson, John (29 May 2020). "Themes from the CPPCC Signal the End of Hong Kong Autonomy—and the Effective End of the "One Country, Two Systems" Framework". Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 7 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Tatlow, Didi Kirsten (3 March 2016). "Advisory Body's Delegates Offer Glimpse Into China's Worries". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- ^ Yu, Xie; Leng, Sidney (4 March 2018). "Tech entrepreneurs dominate as China's political advisers in IT push". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ China's Political Development: Chinese and American Perspectives. Brookings Institution Press. 2014. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-8157-2535-0. JSTOR 10.7864/j.ctt6wpcbw.

- ^ Zheng, Qian (2020). Zheng, Qian (ed.). An Ideological History of the Communist Party of China. Vol. 2. Translated by Sun, Li; Bryant, Shelly. Montreal, Quebec: Royal Collins Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-4878-0391-9.

- ^ a b c d e Grzywacz, Jarek (31 March 2023). "China's 'Two Sessions': More Control, Less Networking". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 25 February 2024. Retrieved 21 January 2024.

- ^ a b Harrell, Stevan (2023). An Ecological History of Modern China. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295751719.

- ^ a b Joske, Alex (9 June 2020). "The party speaks for you: Foreign interference and the Chinese Communist Party's united front system". Australian Strategic Policy Institute. JSTOR resrep25132. Archived from the original on 9 June 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cole, J. Michael; Hsu, Szu-chien (30 July 2020). Insidious Power: How China Undermines Global Democracy. Eastbridge Books. pp. 3–39. ISBN 978-1-78869-213-7.

- ^ a b c d e Lin, Chun (2006). The Transformation of Chinese Socialism. Durham [N.C.]: Duke University Press. pp. 150–151. doi:10.2307/j.ctv113199n. ISBN 978-0-8223-3785-0. JSTOR j.ctv113199n. OCLC 63178961.

- ^ a b c d Li, David Daokui (2024). China's World View: Demystifying China to Prevent Global Conflict. New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393292398.

- ^ Allen-Ebrahimian, Bethany (11 February 2020). "China's 'overseas delegates' connect Beijing to the Chinese diaspora". The Strategist. Australian Strategic Policy Institute. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

These overseas delegates are a way for Beijing to draw on the talent and connections of overseas Chinese to help expand the party's influence and popularity abroad.

- ^ "The National People's Congress of the People's Republic of China". www.npc.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- ^ "Q&A: Roles and functions of Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference". Xinhua News Agency. 3 March 2017. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 13 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Charter of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), Chapter IV: National Committee". Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference. 27 December 2018. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ Davidson, Helen (1 March 2023). "Explainer: what is China's 'two sessions' gathering, and why does it matter?". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 31 March 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ "Charter of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference". Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference. Archived from the original on 2 January 2018. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ a b "The CPPCC". Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference. Archived from the original on 14 August 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2023.

- ^ "中国政协的主要职能和开展工作的主要方式_人民政协_中国政府网". www.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "中国人民政治协商会议全国委员会". www.cppcc.gov.cn. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "中国人民政治协商会议全国委员会常务委员会工作规则". www.hunanzx.gov.cn. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "人民政协报 – 数字报大全 – 云展网". www.yunzhan365.com. Archived from the original on 31 March 2024. Retrieved 31 March 2024.

- ^ "Charter of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), Chapter II: General Organizational Principles". Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference. 27 December 2018. Archived from the original on 31 October 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2023.