List of patriarchs of the Church of the East

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern Christianity |

|---|

|

The Patriarch of the Church of the East (also known as Patriarch of Babylon, Patriarch of the East, the Catholicos-Patriarch of the East or the Grand Metropolitan of the East)[1][2][3] is the patriarch, or leader and head bishop (sometimes referred to as Catholicos or universal leader) of the Church of the East. The position dates to the early centuries of Christianity within the Sassanid Empire, and the church has been known by a variety of names, including the Church of the East, Nestorian Church, the Persian Church, the Sassanid Church, or East Syrian.[4] In the 16th and 17th century the Church, by now restricted to its original Assyrian homeland in Upper Mesopotamia, experienced a series of splits, resulting in a series of competing patriarchs and lineages. Today, the three principal churches that emerged from these splits, the Assyrian Church of the East, Ancient Church of the East and the Chaldean Catholic Church, each have their own patriarch – the Patriarch of the Assyrian Church of the East, the Patriarch of the Ancient Church of the East and the Patriarch of Baghdad of the Chaldeans, respectively.

List of patriarchs until the schism of 1552

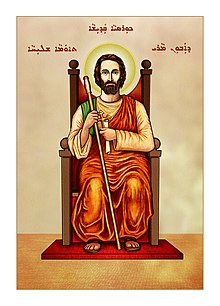

[edit]According to Church legend, the Apostleship of Edessa (Assyria) is alleged to have been founded by Shimun Keepa (Saint Peter) (33–64),[5] Thoma Shlikha, (Saint Thomas), Tulmay (St. Bartholomew the Apostle) and of course Mar Addai (St. Thaddeus) of the Seventy disciples. Saint Thaddeus was martyred c.66 AD.

Early bishops

[edit]- 1. Mar Thoma Shliha (c.34–50)

- 2. Mar Addai Shliha (c.50-66)[6]

- 3. Mar Aggai (c.66–81). First successor to the Apostleship of his spiritual director the Apostle Mar Addai, one of the Seventy disciples. He in turn was the spiritual director of Mar Mari.

- 4. Palut of Edessa (c.81–87) renamed Mar Mari (c.87 – c.121).[7] During his days a bishopric was formally established at Seleucia-Ctesiphon.

- 5. Abris (Abres or Ahrasius) (121–148 AD)[7]

- 6. Abraham (Abraham I of Kashker) (148–171 AD)[7]

- 7. Yaʿqob I (Mar Yacob I) (c. 172–190 AD) son of his predecessor Abraham.[7]

- 8. Ebid M’shikha (191–203)

- 9. Ahadabui (Ahha d'Aboui) (204–220 AD) First bishop of the East to get status as Catholicos. Ordained in 231 AD in Jerusalem[8]

- 10. Shahaloopa of Kashker (Shahlufa) (220–266 AD)

Bishops of Seleucia-Ctesiphon

[edit]Around 280, visiting bishops consecrated Papa bar Aggai as Bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, thereby establishing the succession.[12] With him, heads of the church took the title Catholicos.

- 11. Papa bar Aggai (c. 280–316 AD died 336)

- 12. Simeon Barsabae (coadjutor 317–336, Catholicos from 337–341 AD)

- 13. Shahdost (Shalidoste) (341–343 AD)[13]

- 14. Barbaʿshmin (Barbashmin) (343–346 AD). The apostolic see of Edessa is completely abandoned in 345 AD due to persecutions against the Church of the East.

- 15. Tomarsa (Toumarsa) (346–370 AD)

- 16. Qayyoma (Qaioma) (371–399 AD)

Metropolitans of Seleucia-Ctesiphon

[edit]Isaac was recognised as 'Grand Metropolitan' and Primate of the Church of the East at the Synod of Seleucia-Ctesiphon in 410. The acts of this Synod were later edited by the Patriarch Joseph (552–567) to grant him the title of Catholicos as well. This title for Patriarch Isaac in fact only came into use towards the end of the fifth century.

- 17. Isaac (399–410 AD)

- 18. Ahha (Ahhi) (410–414 AD)

- 19. Yahballaha I (Yab-Alaha I) (415–420 AD)

- 20. Maʿna (Maana) (420 AD)

- 21. Farbokht (Frabokht) (421 AD)

Catholicoi of Seleucia-Ctesiphon

[edit]With Dadisho, the significant disagreement on the dates of the Catholicoi in the sources start to converge. In 424, under Mar Dadisho I, the Church of the East declared itself independent of all the Church of the West (Emperor Justinian's Pentarchy); thereafter, its Catholicoi began to use the additional title of Patriarch.[12] During his reign, the Council of Ephesus in 431 denounced Nestorianism.

- 22. Dadishoʿ (Dadishu I) 421–456 AD)

- 23. Babowai (Babwahi) (457–484 AD)

- 24. Barsauma (484–485) opposed by

- Acacius (Aqaq-Acace) (485–496/8 AD)

- 25. Babai (497–503)

- 26. Shila (503–523)

- 27. Elishaʿ (524–537)

- Narsai intrusus (524–537)

- 28. Paul (539)

- 29. Aba I (540–552)

In 544 the Synod of Mar Aba I adopted the ordinances of the Council of Chalcedon.[14]

- 30. Joseph (552–556/567 AD)

- 31. Ezekiel (567–581)

- 32. Ishoʿyahb I (582–595)

- 33. Sabrishoʿ I (596–604)

- 34. Gregory (605–609)

- vacant (609–628)

- Babai the Great (coadjutor) 609–628; together with Abba (coadjutor) 609–628

- vacant (609–628)

From 628, the Maphrian also began to use the title Catholicos. See the List of Maphrians for details.

- 35. Ishoʿyahb II (628–645)

- 36. Maremmeh (646–649)

- 37. Ishoʿyahb III (649–659)

- 38. Giwargis I (661–680)

- 39. Yohannan I (680–683)

- vacant (683–685)

- 40. Hnanishoʿ I (686–698)

- Yohannan the Leper intrusus (691–693)

- vacant (698–714)

- 41. Sliba-zkha (714–728)

- vacant (728–731)

- 42. Pethion (731–740)

- 43. Aba II (741–751)

- 44. Surin (753)

- 45. Yaʿqob II (753–773)

- 46. Hnanishoʿ II (773–780)

In 775, the seat transferred from Seleucia-Ctesiphon to Baghdad, the recently established capital of the ʿAbbasid caliphs.[15]

- 47. Timothy I (780–823)

- 48. Ishoʿ Bar Nun (823–828)

- 49. Giwargis II (828–831)

- 50. Sabrishoʿ II (831–835)

- 51. Abraham II (837–850)

- vacant (850–853)

- 52. Theodosius (853–858)

- vacant (858–860)

- 53. Sargis (860–872)

- vacant (872–877)

- 54. Israel of Kashkar intrusus (877)

- 55. Enosh (877–884)

- 56. Yohannan II bar Narsai (884–891)

- 57. Yohannan III (893–899)

- 58. Yohannan IV Bar Abgar (900–905)

- 59. Abraham III (906–937)

- 60. Emmanuel I (937–960)

- 61. Israel (961)

- 62. ʿAbdishoʿ I (963–986)

- 63. Mari (987–999)

- 64. Yohannan V (1000–1011)

- 65. Yohannan VI bar Nazuk (1012–1016)

- vacant (1016–1020)

- 66. Ishoʿyahb IV bar Ezekiel (1020–1025)

- vacant (1025–1028)

- 67. Eliya I (1028–1049)

- 68. Yohannan VII bar Targal (1049–1057)

- vacant (1057–1064)

- 69. Sabrishoʿ III (1064–1072)

- 70. ʿAbdishoʿ II ibn al-ʿArid (1074–1090)

- 71. Makkikha I (1092–1110)

- 72. Eliya II Bar Moqli (1111–1132)

- 73. Bar Sawma (1134–1136)

- vacant (1136–1139)

- 74. ʿAbdishoʿ III Bar Moqli (1139–1148)

- 75. Ishoʿyahb V (1149–1176)

- 76. Eliya III (1176–1190)

- 77. Yahballaha II (1190–1222)

- 78. Sabrishoʿ IV Bar Qayyoma (1222–1224)

- 79. Sabrishoʿ V ibn al-Masihi (1226–1256)

- 80. Makkikha II (1257–1265)

- 81. Denha I (1265–1281)

- 82. Yahballaha III (1281–1317) The Patriarchal Seat transferred to Maragha

- 83. Timothy II (1318–c. 1332)

- vacant (c. 1332–c. 1336)

- 84. Denha II (1336/7–1381/2)

- 85. Shemʿon II (c. 1385 – c. 1405) (dates uncertain)

- 86. Eliya IV (c. 1405 – c. 1425) (dates uncertain)

- 87 Shemʿon III (c. 1425 – c. 1450) (existence uncertain)

- 88. Shemʿon IV Basidi (c.1450 – 1497)

- 89. Shemʿon V (1497–1501)

- 90. Eliya V (1502–1503)

- 91. Shemʿon VI (1504–1538)

- 92. Shemʿon VII Ishoʿyahb (1539–1558)

Patriarchal lines from the schism of 1552 until 1830

[edit]By the Schism of 1552 the Church of the East was divided into many splinters but two main factions, of which one entered into full communion with the Catholic Church and the other remained independent. A split in the former line in 1681 resulted in a third faction.

|

1. Eliya line

In 1780, a group split from the Eliya line and elected:

In 1830, following the death of the Amid patriarchal administrator Augustine Hindi, he was recognised by the Vatican as patriarch of Babylon of the Chaldeans and the Mosul and Amid patriarchates were united under his leadership. This event marked the birth of the since unbroken patriarchal line of the Chaldean Catholic Church.[23][24] |

2. Shemʿon line

Shemʿon line reintroduced hereditary succession in 1600; not recognised by Rome; moved to Qochanis

Shemʿon line in Qochanis formally broke communion with Rome:

|

3. Josephite line

|

The Eliya line (1) in Alqosh ended in 1804, having lost most of its followers to Yohannan VIII Hormizd, a member of the same family, who became a Catholic and in 1828, after the death of a rival candidate, a nephew of the last recognized patriarch of the Josephite line in Amid (3), was chosen as Catholic patriarch. Mosul then became the residence of the head of the Chaldean Catholic Church until the transfer to Baghdad in the mid-20th century. For subsequent Chaldean Catholic patriarchs, see List of Chaldean Catholic patriarchs of Baghdad.

The Shemʿon line (2) remained the only line not in communion with the Catholic Church. In 1976 it officially adopted the name "Assyrian Church of the East".[25][26] For subsequent patriarchs in this line, see List of patriarchs of the Assyrian Church of the East.

Numeration of the Eliya line patriarchs

[edit]Since patriarchs of the Eliya line bore the same name (Syriac: ܐܠܝܐ / Elīyā) without using any pontifical numbers, later researchers were faced with several challenges, while trying to implement long standing historiographical practice of individual numeration. First attempts were made by early researchers during the 18th and 19th century, but their numeration was later (1931) revised by Eugène Tisserant, who also believed that during the period from 1558 to 1591 there were two successive Eliya patriarchs, numbered as VI (1558-1576) and VII (1576-1591), and in accordance with that he also assigned numbers (VIII-XIII) to their successors.[27] That numeration was accepted and maintained by several other scholars.[28][29] In 1966 and 1969, the issue was reexamined by Albert Lampart and William Macomber, who concluded that in the period from 1558 to 1591 there was only one patriarch (Eliya VI), and in accordance with that appropriate numbers (VII-XII) were reassigned to his successors.[30][31] In 1999, same conclusion was reached by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, who presented additional evidence in favor of the new numeration.[32] Revised numeration was accepted in modern scholarly works,[33][34][35][36][37][38][39] with one notable exception.

Tisserant's numeration is still advocated by David Wilmshurst, who does acknowledge the existence of only one Eliya patriarch during the period from 1558 to 1591, but counts him as Eliya "VII" and his successors as "VIII" to "XIII", without having any existing patriarch designated as Eliya VI in his works,[40][17][41] an anomaly noticed by other scholars,[36][38][39] but left unexplained and uncorrected by Wilmshurst, even after the additional affirmation of proper numbering, by Samuel Burleson and Lucas van Rompay, in the Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage (2011).[37]

See also

[edit]- List of patriarchs of the Assyrian Church of the East

- List of Chaldean Catholic patriarchs of Baghdad

- Ancient Church of the East

- Catholicose of the East

- Patriarch of the East

- Patriarchal Province of Seleucia-Ctesiphon

References

[edit]- ^ Baum & Winkler (2003), p. 10.

- ^ Coakley (1999), p. 65, 66: "Catholikos-Patriarchs of the East who served on the throne of the church of koke in Seleucia-Ktesiphon".

- ^ Walker 1985, p. 172: "this church had as its head a "catholicos" who came to be styled "Patriarch of the East" and had his seat originally at Seleucia-Ctesiphon (after 775 it was shifted to Baghdad)".

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 4.

- ^ I Peter, 1:1 and 5:13

- ^ Thomasine Church Patriarchs

- ^ a b c d Broadhead 2010, p. 123.

- ^ Council.https://gedsh.bethmardutho.org/entry/Church-East-Uniate-Continuation

- ^ "Histoire nestorienne inédite: Chronique de Séert. Première partie."

- ^ Council.https://gedsh.bethmardutho.org/entry/Church-East-Uniate-Continuation

- ^ Baumer, Christoph (2016). The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity. p. 330. ISBN 9781838609344.

- ^ a b Stewart 1928, p. 15.

- ^ St. Sadoth, Bishop of Seleucia and Ctesiphon, with 128 Companions, Martyrs.

- ^ Meyendorff 1989, p. 287-289.

- ^ Vine 1937, p. 104.

- ^ Murre van den Berg 1999, p. 243-244.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Wilmshurst 2011, p. 477.

- ^ Murre van den Berg 1999, p. 244-245.

- ^ Murre van den Berg 1999, p. 245.

- ^ a b Murre van den Berg 1999, p. 246.

- ^ Murre van den Berg 1999, p. 247.

- ^ Murre van den Berg 1999, p. 248.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 29-30.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 120-122.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 4.

- ^ Butts 2017, p. 604.

- ^ Tisserant 1931, p. 261-263.

- ^ Mooken 1983, p. 21.

- ^ Fiey 1993, p. 37.

- ^ Lampart 1966, p. 53-54, 64.

- ^ Macomber 1969, p. 263-273.

- ^ Murre van den Berg 1999, p. 235–264.

- ^ Coakley 2001, p. 122.

- ^ Baum & Winkler 2003, p. 116, 174.

- ^ Baum 2004, p. 232.

- ^ a b Hage 2007, p. 473.

- ^ a b Burleson & Rompay 2011, p. 481-491.

- ^ a b Jakob 2014, p. 96.

- ^ a b Borbone 2014, p. 224.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2000, p. 3, 355.

- ^ Wilmshurst 2019, p. 799, 804.

Bibliography

[edit]- Assemani, Giuseppe Luigi (1775). De catholicis seu patriarchis Chaldaeorum et Nestorianorum commentarius historico-chronologicus. Roma.

- Assemani, Giuseppe Luigi (2004). History of the Chaldean and Nestorian Patriarchs. Piscataway, New Jersey: Gorgias Press.

- Baum, Wilhelm; Winkler, Dietmar W. (2003). The Church of the East: A Concise History. London-New York: Routledge-Curzon. ISBN 9781134430192.

- Baum, Wilhelm (2004). "Die sogenannten Nestorianer im Zeitalter der Osmanen (15. bis 19. Jahrhundert)". Zwischen Euphrat und Tigris: Österreichische Forschungen zum Alten Orient. Wien: LIT Verlag. pp. 229–246. ISBN 9783825882570.

- Baumer, Christoph (2006). The Church of the East: An Illustrated History of Assyrian Christianity. London-New York: Tauris. ISBN 9781845111151.

- Benjamin, Daniel D. (2008). The Patriarchs of the Church of the East. Piscataway: Gorgias Press. ISBN 9781463211059.

- Borbone, Pier Giorgio (2014). "The Chaldean Business: The Beginnings of East Syriac Typography and the Profession of Faith of Patriarch Elias". Miscellanea Bibliothecae Apostolicae Vaticanae. 20: 211–258.

- Broadhead, Edwin K. (2010). Jewish Ways of Following Jesus: Redrawing the Religious Map of Antiquity. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 9783161503047.

- Burleson, Samuel; Rompay, Lucas van (2011). "List of Patriarchs of the Main Syriac Churches in the Middle East". Gorgias Encyclopedic Dictionary of the Syriac Heritage. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. pp. 481–491.

- Butts, Aaron M. (2017). "Assyrian Christians". In Frahm, Eckart (ed.). A Companion to Assyria. Malden: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 599–612. doi:10.1002/9781118325216. ISBN 9781118325216.

- Coakley, James F. (1999). "The Patriarchal List of the Church of the East". After Bardaisan: Studies on Continuity and Change in Syriac Christianity. Louvain: Peeters Publishers. pp. 65–84. ISBN 9789042907355.

- Coakley, James F. (2001). "Mar Elia Aboona and the History of the East Syrian Patriarchate". Oriens Christianus. 85: 119–138. ISBN 9783447042871.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1970). Jalons pour une histoire de l'Église en Iraq. Louvain: Secretariat du CSCO.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1979) [1963]. Communautés syriaques en Iran et Irak des origines à 1552. London: Variorum Reprints. ISBN 9780860780519.

- Fiey, Jean Maurice (1993). Pour un Oriens Christianus Novus: Répertoire des diocèses syriaques orientaux et occidentaux. Beirut: Orient-Institut. ISBN 9783515057189.

- Foster, John (1939). The Church of the T'ang Dynasty. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

- Hage, Wolfgang (2007). Das orientalische Christentum. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag. ISBN 9783170176683.

- Jakob, Joachim (2014). Ostsyrische Christen und Kurden im Osmanischen Reich des 19. und frühen 20. Jahrhunderts. Münster: LIT Verlag. ISBN 9783643506160.

- Lampart, Albert (1966). Ein Märtyrer der Union mit Rom: Joseph I. 1681-1696, Patriarch der Chaldäer. Köln: Benziger Verlag.

- Macomber, William F. (1969). "A Funeral Madraša on the Assassination of Mar Hnanišo". Mémorial Mgr Gabriel Khouri-Sarkis (1898-1968). Louvain: Imprimerie orientaliste. pp. 263–273.

- Malech, George D.; Malech, Nestorius G. (1910). History of the Syrian nation and the Old Evangelical-Apostolic Church of the East: From Remote Antiquity to the Present Time. Minneapolis: Author's edition.

- Meyendorff, John (1989). Imperial unity and Christian divisions: The Church 450-680 A.D. The Church in history. Vol. 2. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 9780881410563.

- Mooken, Aprem (1983). The Chaldean Syrian Church of the East. Delhi: National Council of Churches in India.

- Murre van den Berg, Heleen H. L. (1999). "The Patriarchs of the Church of the East from the Fifteenth to Eighteenth Centuries" (PDF). Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 2 (2): 235–264. doi:10.31826/hug-2010-020119. S2CID 212688640.

- Stewart, John (1928). Nestorian Missionary Enterprise: A Church on Fire. Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark.

- Tang, Li; Winkler, Dietmar W., eds. (2013). From the Oxus River to the Chinese Shores: Studies on East Syriac Christianity in China and Central Asia. Münster: LIT Verlag. ISBN 9783643903297.

- Tfinkdji, Joseph (1914). "L' église chaldéenne catholique autrefois et aujourd'hui". Annuaire Pontifical Catholique. 17: 449–525.

- Tisserant, Eugène (1931). "L'Église nestorienne". Dictionnaire de théologie catholique. Vol. 11. Paris: Letouzey et Ané. pp. 157–323.

- Vine, Aubrey R. (1937). The Nestorian Churches. London: Independent Press.

- Vosté, Jacques Marie (1930). "Les inscriptions de Rabban Hormizd et de N.-D. des Semences près d'Alqoš (Iraq)". Le Muséon. 43: 263–316.

- Vosté, Jacques Marie (1931). "Mar Iohannan Soulaqa, premier Patriarche des Chaldéens, martyr de l'union avec Rome (†1555)". Angelicum. 8: 187–234.

- Wigram, William Ainger (1910). An Introduction to the History of the Assyrian Church or The Church of the Sassanid Persian Empire 100-640 A.D. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. ISBN 9780837080789.

- Wilmshurst, David (2000). The Ecclesiastical Organisation of the Church of the East, 1318–1913. Louvain: Peeters Publishers. ISBN 9789042908765.

- Wilmshurst, David (2011). The martyred Church: A History of the Church of the East. London: East & West Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781907318047.

- Wilmshurst, David (2019). "The patriarchs of the Church of the East". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 799–805. ISBN 9781138899018.

- Walker, Williston (1985) [1918]. A history of the Christian Church. New York: Scribner. ISBN 9780684184173.