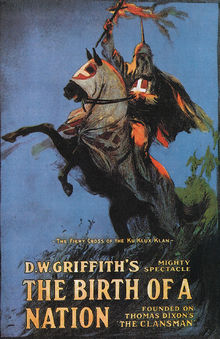

The Birth of a Nation

| The Birth of a Nation | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | D. W. Griffith |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Clansman by Thomas Dixon Jr. |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Billy Bitzer |

| Edited by | D. W. Griffith |

| Music by | Joseph Carl Breil |

Production company | David W. Griffith Corp. |

| Distributed by | Epoch Producing Co. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 12 reels 133–193 minutes[note 1][2] |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $100,000+[3] |

| Box office | $50–100 million[4] |

The Birth of a Nation is a 1915 American silent epic drama film directed by D. W. Griffith and starring Lillian Gish. The screenplay is adapted from Thomas Dixon Jr.'s 1905 novel and play The Clansman. Griffith co-wrote the screenplay with Frank E. Woods and produced the film with Harry Aitken.

The Birth of a Nation is a landmark of film history,[5][6] lauded for its technical virtuosity.[7] It was the first non-serial American 12-reel film ever made.[8] Its plot, part fiction and part history, chronicles the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth and the relationship of two families in the Civil War and Reconstruction eras over the course of several years—the pro-Union (Northern) Stonemans and the pro-Confederacy (Southern) Camerons. It was originally shown in two parts separated by an intermission, and it was the first American-made film to have a musical score for an orchestra. It helped to pioneer closeups and fadeouts, and it includes a carefully staged battle sequence with hundreds of extras made to look like thousands.[9] It came with a 13-page Souvenir Program.[10] It was the first motion picture to be screened inside the White House, viewed there by President Woodrow Wilson, his family, and members of his cabinet.

The film was controversial even before its release and it has remained so ever since; it has been called "the most controversial film ever made in the United States"[11]: 198 and "the most reprehensibly racist film in Hollywood history."[12] The film has been denounced for its racist depiction of African Americans.[7] The film portrays its black characters (many of whom are played by white actors in blackface) as unintelligent and sexually aggressive toward white women. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK), a white supremacist far-right hate group, is portrayed as a heroic force that protects white women and maintains white supremacy.[13][14]

Popular among white audiences nationwide upon its release, the film's success was both a consequence of and a contributor to racial segregation throughout the U.S.[15] In response to the film's depictions of black people and Civil War history, African Americans across the U.S. organized and protested. In Boston and other localities, black leaders and the NAACP spearheaded an unsuccessful campaign to have it banned on the basis that it inflamed racial tensions and could incite violence.[16] It was also denied release in the state of Ohio and the cities of Chicago, Denver, Pittsburgh, St. Louis, and Minneapolis. Griffith's indignation at efforts to censor or ban the film motivated him to produce Intolerance the following year.[17] A 2023 study found that screenings of the film during its original release were linked to a spike in racist violence.

In spite of its divisiveness, The Birth of a Nation was a massive commercial success across the nation—grossing far more than any previous motion picture—and it profoundly influenced both the film industry and American culture. Adjusted for inflation, the film remains one of the highest-grossing films ever made. It has been acknowledged as an inspiration for the rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan, which took place only a few months after its release. In 1992, the Library of Congress deemed the film "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.[18][19]

Plot

[edit]Part 1: Civil War of United States

[edit]

Phil, the elder son of the Stonemans (a Northern family), falls in love with Margaret Cameron (the daughter of a Southern family), during a visit to the Cameron estate in South Carolina. There, Margaret's brother Ben idolizes a picture of Elsie Stoneman, Phil's sister. When the Civil War arrives, the young men of both families enlist in their respective armies. The younger Stoneman and two of the Cameron brothers die in combat. Meanwhile, a black militia attacks the Cameron home and is routed by Confederate soldiers who save the Cameron women. Leading the final charge at the Siege of Petersburg, Ben Cameron earns the nickname of "the Little Colonel," but is also wounded and captured. He is then taken to a Union military hospital in Washington, D.C.

During his stay at the hospital, he learns that he will be hanged. Working there as a nurse is Elsie Stoneman whose picture he has been carrying. Elsie takes Cameron's mother who traveled there to tend her son and to see Abraham Lincoln. Mrs. Cameron persuades him to pardon Ben. After Lincoln's assassination, his conciliatory postwar policy expires with him. Elsie's father and other Radical Republicans are determined to punish the South.[20]

Part 2: Reconstruction

[edit]Stoneman and his protégé Silas Lynch, a psychopathic mulatto, head to South Carolina to observe the implementation of Reconstruction policies. During the election, in which Lynch is elected lieutenant governor, black people stuff the ballot boxes while many white people are denied the vote. The newly elected members of the South Carolina legislature are mostly black.

Inspired by observing white children pretending to be ghosts to scare black children, Ben fights back by forming the Ku Klux Klan. As a result, Elsie breaks up with him. While going off alone into the woods to fetch water, Flora Cameron is followed by Gus, a freedman and soldier who is now a captain. Gus says that he desires to marry Flora. Uninterested, she rejects him, but Gus keeps insisting. Frightened, she flees into the forest, pursued by Gus. Trapped on a precipice, Flora threatens to jump if he comes any closer. When he does, she leaps to her death. While looking for Flora, Ben sees her jump and holds her as she dies. He then carries her body to the Cameron home. In response, the Klan hunts down Gus, tries him, finds him guilty, lynches him and delivers his corpse to the home of Silas Lynch.

After discovering Gus's murder, Lynch orders a crackdown on the Klan. He also secures the passing of legislation allowing mixed-race marriages. Dr. Cameron is arrested for possessing Ben's Klan regalia, now considered a capital crime. He is rescued by Phil Stoneman and some of his black servants. Together with Margaret Cameron, they flee. When their wagon breaks down, they make their way through the woods to a small hut that is home to two former Union soldiers who agree to hide them.

Congressman Stoneman, Elsie's father, leaves to avoid being connected with Lynch's crackdown. Elsie, learning of Dr. Cameron's arrest, visits Lynch to plead for his release. Lynch, who lusts after Elsie, tries to force her to marry him, which causes her to faint. Stoneman returns, causing Elsie to be placed in another room. At first Stoneman is happy when Lynch says that he wants to marry a white woman, but he is then angered when Lynch says that he wishes to marry Elsie. She breaks a window and cries out for help, getting the attention of undercover Klansman spies. The Klan gathered together, with Ben leading them, ride in to gain control of the town. When news about Elsie reaches Ben, he and others go to her rescue. Lynch is captured while his militia attacks the hut where the Camerons are hiding. However, the Klansmen, with Ben at their head, save them. The next election day, black men find a line of mounted and armed Klansmen outside their homes and are intimidated into not voting. Margaret Cameron marries Phil Stoneman and Elsie Stoneman marries Ben Cameron.

Cast

[edit]

- Credited

- Lillian Gish as Elsie Stoneman

- Mae Marsh as Flora Cameron, the pet (baby) sister

- Henry B. Walthall as Colonel Benjamin Cameron ("The Little Colonel")

- Miriam Cooper as Margaret Cameron, elder sister

- Mary Alden as Lydia Brown, Stoneman's housekeeper

- Ralph Lewis as Austin Stoneman, Leader of the House

- George Siegmann as Silas Lynch

- Walter Long as Gus, the renegade

- Wallace Reid as Jeff, the blacksmith

- Joseph Henabery as Abraham Lincoln

- Elmer Clifton as Phil Stoneman, elder son

- Robert Harron as Tod Stoneman

- Josephine Crowell as Mrs. Cameron

- Spottiswoode Aitken as Dr. Cameron

- George Beranger as Wade Cameron, second son

- Maxfield Stanley as Duke Cameron, youngest son

- Jennie Lee as Mammy, the faithful servant

- Donald Crisp as General Ulysses S. Grant

- Howard Gaye as General Robert E. Lee

- Uncredited[21]

- Harry Braham as Cameron's faithful servant

- Edmund Burns as Klansman

- David Butler as Union soldier / Confederate soldier

- William Freeman as Jake, a mooning sentry at Federal hospital

- Sam De Grasse as Senator Charles Sumner

- Olga Grey as Laura Keene

- Russell Hicks

- Elmo Lincoln as ginmill owner / slave auctioneer

- Eugene Pallette as Union soldier

- Harry Braham as Jake / Nelse

- Charles Stevens as volunteer

- Madame Sul-Te-Wan as woman with gypsy shawl

- Raoul Walsh as John Wilkes Booth

- Lenore Cooper as Elsie's maid

- Violet Wilkey as young Flora

- Tom Wilson as Stoneman's servant

- Donna Montran as belles of 1861

- Alberta Lee as Mrs. Mary Todd Lincoln

- Allan Sears as Klansmen

- Dark Cloud as General at Appomattox Surrender

- Vester Pegg

- Alma Rubens

- Mary Wynn

- Jules White

- Monte Blue

- Gibson Gowland

- Fred Burns

- Charles King

Production

[edit]1911 version

[edit]In 1911, the Kinemacolor Company of America produced a lost film in Kinemacolor titled The Clansman. It was filmed in the southern United States and directed by William F. Haddock. According to different sources, the ten-reel film was either completed by January 1912 or left uncompleted with a little more than a reel of footage. There are several speculated reasons why the film production failed including unresolved legal issues regarding the rights to the story, financial issues, problems with the Kinemacolor process, and poor direction. Frank E. Woods, the films scriptwriter, showed his work to Griffith, who was inspired to create his own film adaptation of the novel, titled The Birth of a Nation.[22][23][24]

Inspiration

[edit]Many of the fictional characters in the film are based on real historical figures. Abolitionist U.S. Representative Austin Stoneman is based on the Reconstruction-era Representative Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania.[25][26] Ben Cameron is modeled after Leroy McAfee.[27] Silas Lynch was modeled after Alonzo J. Ransier and Richard Howell Gleaves.[28][29]

Development

[edit]After the failure of the Kinemacolor project, in which Dixon was willing to invest his own money,[30]: 330 he began visiting other studios to see if they were interested.[31]: 421 In late 1913, Dixon met the film producer Harry Aitken, who was interested in making a film out of The Clansman. Through Aitken, Dixon met Griffith.[31]: 421 Like Dixon, Griffith was a Southerner, a fact that Dixon points out;[32]: 295 Griffith's father served as a colonel in the Confederate States Army and, like Dixon, viewed Reconstruction negatively. Griffith believed that a passage from The Clansman where Klansmen ride "to the rescue of persecuted white Southerners" could be adapted into a great cinematic sequence.[33] Griffith first announced his intent to adapt Dixon's play to Gish and Walthall after filming Home, Sweet Home in 1914.[28]

Birth of a Nation "follows The Clansman [the play] nearly scene by scene."[34]: xvii While some sources also credit The Leopard's Spots as source material, Russell Merritt attributes this to "the original 1915 playbills and program for Birth which, eager to flaunt the film's literary pedigree, cited both The Clansman and The Leopard's Spots as sources."[35] According to Karen Crowe, "[t]here is not a single event, word, character, or circumstance taken from The Leopard's Spots.... Any likenesses between the film and The Leopard's Spots occur because some similar scenes, circumstances, and characters appear in both books."[34]: xvii–xviii

Griffith agreed to pay Thomas Dixon $10,000 (equivalent to $304,186 in 2023) for the rights to his play The Clansman. Since he ran out of money and could afford only $2,500 of the original option, Griffith offered Dixon 25 percent interest in the picture. Dixon reluctantly agreed, and the unprecedented success of the film made him rich. Dixon's proceeds were the largest sum any author had received [up to 2007] for a motion picture story and amounted to several million dollars.[36] The American historian John Hope Franklin suggested that many aspects of the script for The Birth of a Nation appeared to reflect Dixon's concerns more than Griffith's, as Dixon had an obsession in his novels of describing in loving detail the lynchings of black men which did not reflect Griffith's interests.[31]: 422–423

Filming

[edit]

Griffith began filming on July 4, 1914[37] and was finished by October 1914.[31]: 421 Some filming took place in Big Bear Lake, California.[38] Griffith took over the Hollywood studio of Kinemacolor. West Point engineers provided technical advice on the American Civil War battle scenes providing Griffith with the artillery used in the film. Much of the filming was done on the Griffith Ranch in San Fernando Valley, with the Petersburg scenes being shot at what is today Forest Lawn Memorial Park and other scenes being shot in Whittier and Ojai Valley.[39][40] The film's war scenes were influenced by Robert Underwood Johnson's book Battles and Leaders of the Civil War, Harper's Pictorial History of the Civil War, The Soldier in Our Civil War, and Mathew Brady's photography.[28]

Many of the African Americans in the film were portrayed by white actors in blackface. Griffith initially claimed this was deliberate, stating "on careful weighing of every detail concerned, the decision was to have no black blood among the principals; it was only in the legislative scene that Negroes were used, and then only as 'extra people'." However black extras who had been housed in segregated quarters, including Griffith's acquaintance and frequent collaborator Madame Sul-Te-Wan, can be seen in many other shots of the film.[28]

Griffith's budget started at US$40,000[36] (equivalent to $1,200,000 in 2023[41]) but rose to over $100,000[3] (equivalent to $3,010,000 in 2023[41]).

By the time he finished filming, Griffith had shot approximately 150,000 feet of footage (approximately 36 hours of film), which he edited down to 13,000 feet (just over 3 hours).[37] The film was edited after early screenings in reaction to audience reception, and existing prints of the film are missing footage from the standard version of the film. Evidence exists that the film originally included scenes of white slave traders seizing blacks from West Africa and detaining them aboard a slave ship, Southern congressmen in the House of Representatives, Northerners reacting to the results of the 1860 presidential election, the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment, a Union League meeting, depictions of martial law in South Carolina, and a battle sequence. In addition, several scenes were cut at the insistence of New York Mayor John Purroy Mitchel due to their highly racist content before its release in New York City including a female abolitionist activist recoiling from the body odor of a black boy, black men seizing white women on the streets of Piedmont, and deportations of blacks with the title "Lincoln's Solution". It was also long rumored, including by Griffith's biographer Seymour Stern, that the original film included a rape scene between Gus and Flora before her suicide, but in 1974 the cinematographer Karl Brown denied that such a scene had been filmed.[28]

Score

[edit]

Although The Birth of a Nation is commonly regarded as a landmark for its dramatic and visual innovations, its use of music was arguably no less revolutionary.[42] Though film was still silent at the time, it was common practice to distribute musical cue sheets, or less commonly, full scores (usually for organ or piano accompaniment) along with each print of a film.[43]

For The Birth of a Nation, composer Joseph Carl Breil created a three-hour-long musical score that combined all three types of music in use at the time: adaptations of existing works by classical composers, new arrangements of well-known melodies, and original composed music.[42] Though it had been specifically composed for the film, Breil's score was not used for the February 8, 1915, Los Angeles première of the film at Clune's Auditorium; rather, a score compiled by Carli Elinor was performed in its stead, and this score was used exclusively in West Coast showings. Breil's score was not used until the film debuted in New York at the Liberty Theatre, but it was the score featured in all showings save those on the West Coast.[44][45]

Outside of original compositions, Breil adapted classical music for use in the film, including passages from Der Freischütz by Carl Maria von Weber, Leichte Kavallerie by Franz von Suppé, Symphony No. 6 by Ludwig van Beethoven, and "Ride of the Valkyries" by Richard Wagner, the latter used as a leitmotif during the ride of the KKK.[42] Breil also arranged several traditional and popular tunes that would have been recognizable to audiences at the time, including many Southern melodies; among these songs were "Maryland, My Maryland", "Dixie",[46] "Old Folks at Home," "The Star-Spangled Banner," "America the Beautiful," "The Battle Hymn of the Republic," "Auld Lang Syne," and "Where Did You Get That Hat?"[42][47] DJ Spooky has called Breil's score, with its mix of Dixieland songs, classical music and "vernacular heartland music...an early, pivotal accomplishment in remix culture." He has also cited Breil's use of music by Wagner as influential on subsequent Hollywood films, including Star Wars (1977) and Apocalypse Now (1979).[48]

In his original compositions for the film, Breil wrote numerous leitmotifs to accompany the appearance of specific characters. The principal love theme that was created for the romance between Elsie Stoneman and Ben Cameron was published as "The Perfect Song" and is regarded as the first marketed "theme song" from a film; it was later used as the theme song for the popular radio and television sitcom Amos 'n' Andy.[44][45]

Release

[edit]

Theatrical run

[edit]The first public showing of the film, then called The Clansman, was on January 1 and 2, 1915, at the Loring Opera House in Riverside, California.[49] The second night, it was sold out and people were turned away.[50] It was shown on February 8, 1915, to an audience of 3,000 people at Clune's Auditorium in downtown Los Angeles[51] and ran there for seven months.[52]

At the New York premiere, Dixon spoke on stage when the interlude started halfway through the film, reminding the audience that the dramatic version of The Clansman appeared in that venue nine years previously. "Mr. Dixon also observed that he would have allowed none but the son of a Confederate soldier to direct the film version of The Clansman."[53] An estimated 3 million people watched the film across 6,266 showings in New York City by January 1916.[54]

The film's backers understood that the film needed a massive publicity campaign if they were to cover the immense cost of producing it. A major part of this campaign was the release of the film in a roadshow theatrical release. This allowed Griffith to charge premium prices for tickets, sell souvenirs, and build excitement around the film before giving it a wide release. For several months, Griffith's team traveled to various cities to show the film for one or two nights before moving on. This strategy was immensely successful.[37]

Change of title

[edit]Dixon had seen a screening of the film for an invited audience in New York in early 1915, when the title was still The Clansmen. Struck by the power of the film, he told Griffith that The Clansmen was not an appropriate title, and suggested that it be changed to The Birth of a Nation.[55] The title was changed before the March 2 New York opening.[30]: 329 However, the title was used in the press as early as January 2, 1915,[56][57] while it was still referred to as The Clansman in October.[58]

Special screenings

[edit]White House showing

[edit]The Birth of a Nation was the first movie shown in the White House, in the East Room, on February 18, 1915.[59] (An earlier movie, the Italian Cabiria (1914), was shown on the lawn.) It was attended by President Woodrow Wilson, members of his family, and members of his Cabinet.[60] Both Dixon and Griffith were present.[61]: 126 As put by Dixon, not an impartial source, "it repeated the triumph of the first showing."[32]: 299

There is dispute about Wilson's attitude toward the movie. A newspaper reported that he "received many letters protesting against his alleged action in Indorsing the pictures [sic]" including a letter from Massachusetts Congressman Thomas Chandler Thacher.[60] The showing of the movie had caused "several near-riots".[60] When former Assistant Attorney General William H. Lewis and A. Walters, a bishop of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, called at the White House "to add their protests," President Wilson's private secretary, Joseph Tumulty, showed them a letter he had written to Thacher on Wilson's behalf. According to the letter, Wilson had been "entirely unaware of the character of the play [movie] before it was presented and has at no time expressed his approbation of it. Its exhibition at the White House was a courtesy extended to an old acquaintance."[60] Dixon, in his autobiography, quotes Wilson as saying, when Dixon proposed showing the movie at the White House, that "I am pleased to be able to do this little thing for you, because a long time ago you took a day out of your busy life to do something for me."[32]: 298 What Dixon had done for Wilson was to suggest him for an honorary degree, which Wilson received, from Dixon's alma mater, Wake Forest College.[62]: 512

Dixon had been a fellow graduate student in history with Wilson at The Johns Hopkins University and, in 1913, dedicated his historical novel about Lincoln, The Southerner, to "our first Southern-born president since Lincoln, my friend and collegemate Woodrow Wilson."

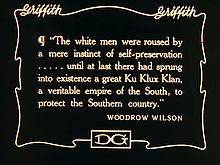

The evidence that Wilson knew "the character of the play" in advance of seeing it is circumstantial but very strong: "Given Dixon's career and the notoriety attached to the play The Clansman, it is not unreasonable to assume that Wilson must have had some idea of at least the general tenor of the film."[62]: 513 The movie was based on a best-selling novel and was preceded by a stage version (play) which was received with protests in several cities—in some cities it was prohibited—and received a great deal of news coverage. Wilson issued no protest when The Washington Evening Star, at that time Washington, D.C.'s "newspaper of record," reported in advance of the showing, in language suggesting a press release from Dixon and Griffiths, that Dixon was "a schoolmate of President Wilson and is an intimate friend" and that Wilson's interest in it "is due to the great lesson of peace it teaches."[59] Wilson, and only Wilson, is quoted by name in the movie for his observations on American history and the title of Wilson's book (History of the American People) is mentioned as well.[62]: 518–519 The three title cards with quotations from Wilson's book read:

"Adventurers swarmed out of the North, as much the enemies of one race as of the other, to cozen, beguile and use the negroes... [Ellipsis in the original.] In the villages the negroes were the office holders, men who knew none of the uses of authority, except its insolences."

"... The policy of the congressional leaders wrought…a veritable overthrow of civilization in the South... in their determination to 'put the white South under the heel of the black South.'" [Ellipses and underscore in the original.]

"The white men were roused by a mere instinct of self-preservation... until at last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan, a veritable empire of the South, to protect the southern country." [Ellipsis in the original.]

In the same book, Wilson has harsh words about the abyss between the original goals of the Klan and that into which it evolved.[63][64] Dixon has been accused of misquoting Wilson.[62]: 518

In 1937, a popular magazine reported that Wilson said of the film, "It is like writing history with lightning. And my only regret is that it is all so terribly true."[65] Wilson over the years had several times used the metaphor of illuminating history as if by lightning and he may well have said it at the time. The accuracy of his saying it was "terribly true" is disputed by historians; there is no contemporary documentation of the remark.[62]: 521 [66] Vachel Lindsay, a popular poet of the time, is known to have referred to the film as "art by lightning flash."[67]

Showing in the Raleigh Hotel ballroom

[edit]The next day, February 19, 1915, Griffith and Dixon held a showing of the film in the Raleigh Hotel ballroom, which they had hired for the occasion. Early that morning, Dixon called on a North Carolina friend, Josephus Daniels, Secretary of the Navy. Daniels set up a meeting that morning for Dixon with Edward Douglass White, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Initially Justice White was not interested in seeing the film, but when Dixon told him it was the "true story" of Reconstruction and the Klan's role in "saving the South", White, recalling his youth in Louisiana, jumped to attention and said: "I was a member of the Klan, sir".[68]: 171–172 With White agreeing to see the film, the rest of the Supreme Court followed. In addition to the entire Supreme Court, in the audience were "many members of Congress and members of the diplomatic corps",[69][70] the Secretary of the Navy, 38 members of the Senate, and about 50 members of the House of Representatives. The audience of 600 "cheered and applauded throughout."[31]: 425 [71][72]

Consequences

[edit]In Griffith's words, the showings to the president and the entire Supreme Court conferred an "honor" upon Birth of a Nation.[62][page needed] Dixon and Griffith used this commercially.

The following day, Griffith and Dixon transported the film to New York City for review by the National Board of Censorship. They presented the film as "endorsed" by the President and the cream of Washington society. The Board approved the film by 15 to 8.[73]: 127

A warrant to close the theater in which the movie was to open was dismissed after a long-distance call to the White House confirmed that the film had been shown there.[32]: 303 [68]: 173

Justice White was very angry when advertising for the film stated that he approved it, and he threatened to denounce it publicly.[62]: 519

Dixon, a racist and white supremacist,[74] clearly was rattled and upset by criticism by African Americans that the movie encouraged hatred against them, and he wanted the endorsement of as many powerful men as possible to offset such criticism.[31] Dixon always vehemently denied having anti-black prejudices—despite the way his books promoted white supremacy—and stated: "My books are hard reading for a Negro, and yet the Negroes, in denouncing them, are unwittingly denouncing one of their greatest friends".[31]: 424

In a letter sent on May 1, 1915, to Joseph P. Tumulty, Wilson's secretary, Dixon wrote: "The real purpose of my film was to revolutionize Northern sentiments by a presentation of history that would transform every man in the audience into a good Democrat... Every man who comes out of the theater is a Southern partisan for life!"[31]: 430 In a letter to President Wilson sent on September 5, 1915, Dixon boasted: "This play is transforming the entire population of the North and the West into sympathetic Southern voters. There will never be an issue of your segregation policy".[31]: 430 Dixon was alluding to the fact that Wilson, upon becoming president in 1913, had allowed cabinet members to impose segregation on federal workplaces in Washington, D.C. by reducing the number of black employees through demotion or dismissal.[75]

New opening titles on re-release

[edit]One famous part of the film was added by Griffith only on the second run of the film[76] and is missing from most online versions of the film (presumably taken from first run prints).[77]

These are the second and third of three opening title cards that defend the film. The added titles read:

A PLEA FOR THE ART OF THE MOTION PICTURE:

We do not fear censorship, for we have no wish to offend with improprieties or obscenities, but we do demand, as a right, the liberty to show the dark side of wrong, that we may illuminate the bright side of virtue—the same liberty that is conceded to the art of the written word—that art to which we owe the Bible and the works of Shakespeare and If in this work we have conveyed to the mind the ravages of war to the end that war may be held in abhorrence, this effort will not have been in vain.

Various film historians have expressed a range of views about these titles. To Nicholas Andrew Miller, this shows that "Griffith's greatest achievement in The Birth of a Nation was that he brought the cinema's capacity for spectacle... under the rein of an outdated, but comfortably literary form of historical narrative. Griffith's models... are not the pioneers of film spectacle... but the giants of literary narrative".[78] On the other hand, S. Kittrell Rushing complains about Griffith's "didactic" title-cards,[79] while Stanley Corkin complains that Griffith "masks his idea of fact in the rhetoric of high art and free expression" and creates a film that "erodes the very ideal" of liberty that he asserts.[80]

Social impact

[edit]KKK support

[edit]Studies have linked the film to greater support for the KKK.[81][82][83] Glorifying the Klan to approving white audiences,[84] the film became a national cultural phenomenon: merchandisers made Ku Klux hats and kitchen aprons, and ushers dressed in white Klan robes for openings. In New York there were Klan-themed balls and, in Chicago that Halloween, thousands of college students dressed in robes for a massive Klan-themed party.[85]

Anti-black violence

[edit]When the film was released, riots broke out in Philadelphia and other major cities in the United States. The film's inflammatory nature was a catalyst for gangs of white people to attack black people. On April 24, 1916, the Chicago American reported that a white man murdered a black teenager in Lafayette, Indiana, after seeing the film, although there has been some controversy as to whether the murderer had actually seen The Birth of a Nation.[86] The mayor of Cedar Rapids, Iowa was the first of twelve mayors to ban the film in 1915 out of concern that it would promote racial prejudice, after meeting with a delegation of black citizens.[87] The NAACP set up a precedent-setting national boycott of the film, likely seen as the most successful effort. Additionally, they organized a mass demonstration when the film was screened in Boston, and it was banned in three states and several cities.[88]

In 2021, a Harvard University research paper found that the film was shown in 606 counties in the United States and that "[o]n average, lynchings in a county rose fivefold in the month after [the film] arrived."[82]A 2023 study in the American Economic Review found that roadshow screenings of the film were associated with a sharp spike in lynchings and race riots between 1915 and 1920.[81]

Contemporary reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]The New York Times called the film "melodramatic" and "inflammatory" in a brief review adding that: "A great deal might be said concerning the spirit revealed in Mr. Dixon's review of the unhappy chapter of Reconstruction and concerning the sorry service rendered by its plucking at old wounds."[89] Variety praised Griffith's direction, claiming he "set such a pace it will take a long time before one will come along that can top it in point of production, acting, photography and direction. Every bit of the film was laid, played and made in America. One may find some flaws in the general running of the picture, but they are so small and insignificant that the bigness and greatness of the entire film production itself completely crowds out any little defects that might be singled out."[90]

Burns Mantle in the New York Daily News noted "an element of excitement that swept a sophisticated audience like a prairie fire in a high wind", while the New York Tribune said it was a "spectacular drama" with "thrills piled upon thrills". The New Republic, however, called it "aggressively vicious and defamatory" and a "spiritual assassination. It degrades the censors that passed it and the white race that endures it".[91]

Box office

[edit]

The box office gross of The Birth of a Nation is not known and has been the subject of exaggeration.[92] When the film opened, the tickets were sold at premium prices. The film played at the Liberty Theater at Times Square in New York City for 44 weeks with tickets priced at $2.20 (equivalent to $66 in 2023).[93] By the end of 1917, Epoch reported to its shareholders cumulative receipts of $4.8 million,[94] and Griffith's own records put Epoch's worldwide earnings from the film at $5.2 million as of 1919,[95] although the distributor's share of the revenue at this time was much lower than the exhibition gross. In the biggest cities, Epoch negotiated with individual theater owners for a percentage of the box office; elsewhere, the producer sold all rights in a particular state to a single distributor (an arrangement known as "state's rights" distribution).[96] The film historian Richard Schickel says that under the state's rights contracts, Epoch typically received about 10% of the box office gross—which theater owners often underreported—and concludes that "Birth certainly generated more than $60 million in box-office business in its first run".[94]

The film was the highest-grossing film until it was overtaken by Gone with the Wind (1939), another film about the Civil War and Reconstruction era.[97][98] By 1940 Time magazine estimated the film's cumulative gross rental (the distributor's earnings) at approximately $15 million.[99] For years Variety had the gross rental listed as $50 million, but in 1977 repudiated the claim and revised its estimate down to $5 million.[94] It is not known for sure how much the film has earned in total, but producer Harry Aitken put its estimated earnings at $15–18 million in a letter to a prospective investor in a proposed sound version.[95] It is likely the film earned over $20 million for its backers and generated $50–100 million in box office receipts.[4] In a 2015 Time article, Richard Corliss estimated the film had earned the equivalent of $1.8 billion adjusted for inflation, a milestone that at the time had only been surpassed by Titanic (1997) and Avatar (2009) in nominal earnings.[100]

Criticism

[edit]Like Dixon's novels and play, Birth of a Nation received considerable criticism, both before and after its premiere. Dixon, who believed the film to be entirely truthful and historically accurate, attributed this to "Sectionalists", i.e. non-Southerners who in Dixon's opinion were hostile to the "truth" about the South.[32]: 301, 303 It was to counter these "sinister forces" and the "dangerous... menace" that Dixon and Griffith sought "the backing" of President Wilson and the Supreme Court.[32]: 296

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) protested at premieres of the film in numerous cities. According to the historian David Copeland, "by the time of the movie's March 3 [1915] premiere in New York City, its subject matter had embroiled the film in charges of racism, protests, and calls for censorship, which began after the Los Angeles branch of the NAACP requested the city's film board ban the movie. Since film boards were composed almost entirely of whites, few review boards initially banned Griffith's picture".[101] The NAACP also conducted a public education campaign, publishing articles protesting the film's fabrications and inaccuracies, organizing petitions against it, and conducting education on the facts of the war and Reconstruction.[102] Because of the lack of success in NAACP's actions to ban the film, on April 17, 1915, NAACP secretary Mary Childs Nerney wrote to NAACP Executive Committee member George Packard: "I am utterly disgusted with the situation in regard to The Birth of a Nation ... kindly remember that we have put six weeks of constant effort of this thing and have gotten nowhere."[103] W. E. B. Du Bois's biographer David Levering Lewis opined that "... The Birth of a Nation and the NAACP helped make each other", in that the NAACP campaign in one sense served as advertising for the film, but that it also "... mobilized thousands of black and white men and women in large cities across the country... who had been unaware of the existence of the [NAACP] or indifferent to it."[104]

Jane Addams, an American social worker and social reformer, and the founder of Hull House, voiced her reaction to the film in an interview published by the New York Post on March 13, 1915, just ten days after the film was released.[105] She stated that "One of the most unfortunate things about this film is that it appeals to race prejudice upon the basis of conditions of half a century ago, which have nothing to do with the facts we have to consider to-day. Even then it does not tell the whole truth. It is claimed that the play is historical: but history is easy to misuse."[105] In New York, Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise told the press after seeing The Birth of a Nation that the film was "an indescribable foul and loathsome libel on a race of human beings".[31]: 426 In Boston, Booker T. Washington wrote a newspaper column asking readers to boycott the film,[31]: 426 while the civil rights activist William Monroe Trotter organized demonstrations against the film, which he predicted was going to worsen race relations. On Saturday, April 10, and again on April 17, Trotter and a group of other blacks tried to buy tickets for the show's premiere at the Tremont Theater and were refused. They stormed the box office in protest, 260 police on standby rushed in, and a general melee ensued. Trotter and ten others were arrested.[106] The following day a huge demonstration was staged at Faneuil Hall.[16][107] In Washington D.C, the Reverend Francis James Grimké published a pamphlet entitled "Fighting a Vicious Film" that challenged the historical accuracy of The Birth of a Nation on a scene-by-scene basis.[31]: 427

Both Griffith and Dixon in letters to the press dismissed African-American protests against The Birth of a Nation.[108] In a letter to The New York Globe, Griffith wrote that his film was "an influence against the intermarriage of blacks and whites".[108] Dixon likewise called the NAACP "the Negro Intermarriage Society" and said it was against The Birth of a Nation "for one reason only—because it opposes the marriage of blacks to whites".[108] Griffith—indignant at the film's negative critical reception—wrote letters to newspapers and published a pamphlet in which he accused his critics of censoring unpopular opinions.[109]

When Sherwin Lewis of The New York Globe wrote a piece that expressed criticism of the film's distorted portrayal of history and said that it was not worthy of constitutional protection because its purpose was to make a few "dirty dollars", Griffith responded that "the public should not be afraid to accept the truth, even though it might not like it". He also added that the man who wrote the editorial was "damaging my reputation as a producer" and "a liar and a coward".[49]

Audience reaction

[edit]

The Birth of a Nation was very popular, despite the film's controversy; it was unlike anything that American audiences had ever seen before.[111] The Los Angeles Times called it "the greatest picture ever made and the greatest drama ever filmed".[112] Mary Pickford said: "Birth of a Nation was the first picture that really made people take the motion picture industry seriously".[113] The producers had 15 "detectives" at the Liberty Theater in New York City "to prevent disorder on the part of those who resent the 'reconstruction period' episodes depicted."[114]

The Reverend Charles Henry Parkhurst argued that the film was not racist, saying that it "was exactly true to history" by depicting freedmen as they were and, therefore, it was a "compliment to the black man" by showing how far black people had "advanced" since Reconstruction.[115] Critic Dolly Dalrymple wrote that, "when I saw it, it was far from silent... incessant murmurs of approval, roars of laughter, gasps of anxiety, and outbursts of applause greeted every new picture on the screen".[110] One man viewing the film was so moved by the scene where Flora Cameron flees Gus to avoid being raped that he took out his handgun and began firing at the screen in an effort to help her.[110] Katharine DuPre Lumpkin recalled watching the film as an 18-year-old in 1915 in her 1947 autobiography The Making of a Southerner: "Here was the black figure—and the fear of the white girl—though the scene blanked out just in time. Here were the sinister men the South scorned and the noble men the South revered. And through it all the Klan rode. All around me people sighed and shivered, and now and then shouted or wept, in their intensity."[116]

Sequel and spin-offs

[edit]D. W. Griffith made a film in 1916, called Intolerance, partly in response to the criticism that The Birth of a Nation received. Griffith made clear within numerous interviews that the film's title and main themes were chosen in response to those who he felt had been intolerant to The Birth of a Nation.[117] A sequel called The Fall of a Nation was released in 1916, depicting the invasion of the United States by a German-led confederation of European monarchies and criticizing pacifism in the context of the First World War. It was the first feature-length sequel in film history.[118] The film was directed by Thomas Dixon Jr., who adapted it from his novel of the same name. Despite its success in the foreign market, the film was not a success among American audiences,[11]: 102 and is now a lost film.[11]: Summary

In 1918, an American silent drama film directed by John W. Noble called The Birth of a Race was released as a direct response to The Birth of a Nation.[119] The film was an ambitious project by producer Emmett Jay Scott to challenge Griffith's film and tell another side of the story, but was ultimately unsuccessful.[120] In 1920, African-American filmmaker Oscar Micheaux released Within Our Gates, a response to The Birth of a Nation. Within Our Gates depicts the hardships faced by African Americans during the era of Jim Crow laws.[121] Griffith's film was remixed in 2004 as Rebirth of a Nation by DJ Spooky.[122] Quentin Tarantino has said that he made his film Django Unchained (2012) to counter the falsehoods of The Birth of a Nation.[123]

Influence

[edit]In November 1915, William Joseph Simmons revived the Klan in Atlanta, Georgia, holding a cross burning at Stone Mountain.[31]: 430 [124] The historian John Hope Franklin observed that, had it not been for The Birth of a Nation, the Klan might not have been reborn.[31]: 430–431

Modern reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]

Released in 1915, The Birth of a Nation has been considered as innovative among its contemporaries in the early days of film. According to the film historian Kevin Brownlow, the film was "astounding in its time" and initiated "so many advances in film-making technique that it was rendered obsolete within a few years".[125] The content of the work, however, has received widespread criticism for its blatant racism. Film critic Roger Ebert wrote:

Certainly The Birth of a Nation (1915) presents a challenge for modern audiences. Unaccustomed to silent films and uninterested in film history, they find it quaint and not to their taste. Those evolved enough to understand what they are looking at find the early and wartime scenes brilliant, but cringe during the postwar and Reconstruction scenes, which are racist in the ham-handed way of an old minstrel show or a vile comic pamphlet.[126]

Despite its controversial story, the film has been praised by film critics, with Ebert mentioning its use as a historical tool: "The Birth of a Nation is not a bad film because it argues for evil. Like Riefenstahl's Triumph of the Will, it is a great film that argues for evil. To understand how it does so is to learn a great deal about film, and even something about evil."[126]

According to a 2002 article in the Los Angeles Times, the film facilitated the refounding of the Ku Klux Klan in 1915.[127] History.com states that "There is no doubt that Birth of a Nation played no small part in winning wide public acceptance" for the KKK, and that throughout the film "African Americans are portrayed as brutish, lazy, morally degenerate, and dangerous."[128] David Duke used the film to recruit Klansmen in the 1970s.[129]

In 2013, the American critic Richard Brody wrote The Birth of a Nation was:

... a seminal commercial spectacle but also a decisively original work of art—in effect, the founding work of cinematic realism, albeit a work that was developed to pass lies off as reality. It's tempting to think of the film's influence as evidence of the inherent corruption of realism as a cinematic mode—but it's even more revealing to acknowledge the disjunction between its beauty, on the one hand, and, on the other, its injustice and falsehood. The movie's fabricated events shouldn't lead any viewer to deny the historical facts of slavery and Reconstruction. But they also shouldn't lead to a denial of the peculiar, disturbingly exalted beauty of Birth of a Nation, even in its depiction of immoral actions and its realization of blatant propaganda. The worst thing about The Birth of a Nation is how good it is. The merits of its grand and enduring aesthetic make it impossible to ignore and, despite its disgusting content, also make it hard not to love. And it's that very conflict that renders the film all the more despicable, the experience of the film more of a torment—together with the acknowledgment that Griffith, whose short films for Biograph were already among the treasures of world cinema, yoked his mighty talent to the cause of hatred (which, still worse, he sincerely depicted as virtuous).[123]

Brody also argued that Griffith unintentionally undercut his own thesis in the film, citing the scene before the Civil War when the Cameron family offers up lavish hospitality to the Stoneman family who travel past mile after mile of slaves working the cotton fields of South Carolina to reach the Cameron home. Brody maintained that a modern audience can see that the wealth of the Camerons comes from the slaves, forced to do back-breaking work picking the cotton. Likewise, Brody argued that the scene where people in South Carolina celebrate the Confederate victory at the Battle of Bull Run by dancing around the "eerie flare of a bonfire" implies "a dance of death", foreshadowing the destruction of Sherman's March that was to come. In the same way, Brody wrote that the scene where the Klan dumps Gus's body off at the doorstep of Lynch is meant to have the audience cheering, but modern audiences find the scene "obscene and horrifying". Finally, Brody argued that the end of the film, where the Klan prevents defenseless African Americans from exercising their right to vote by pointing guns at them, today seems "unjust and cruel".[123]

In an article for The Atlantic, film critic Ty Burr deemed The Birth of a Nation the most influential film in history while criticizing its portrayal of black men as savage.[130] Richard Corliss of Time wrote that Griffith "established in the hundreds of one- and two-reelers he directed a cinematic textbook, a fully formed visual language, for the generations that followed. More than anyone else—more than all others combined—he invented the film art. He brought it to fruition in The Birth of a Nation." Corliss praised the film's "brilliant storytelling technique" and noted that "The Birth of a Nation is nearly as antiwar as it is antiblack. The Civil War scenes, which consume only 30 minutes of the extravaganza, emphasize not the national glory but the human cost of combat. ... Griffith may have been a racist politically, but his refusal to find uplift in the South's war against the Union—and, implicitly, in any war at all—reveals him as a cinematic humanist."[100]

Accolades

[edit]In 1992, the U.S. Library of Congress deemed the film "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" and selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry.[131] The American Film Institute ranked it #44 within the AFI's 100 Years...100 Movies list in 1998.[132]

Historical portrayal

[edit]The film remains controversial due to its interpretation of American history. University of Houston historian Steven Mintz summarizes its message as follows: "Reconstruction was an unmitigated disaster, African-Americans could never be integrated into white society as equals, and the violent actions of the Ku Klux Klan were justified to reestablish honest government".[133] The South is portrayed as a victim. The first overt mentioning of the war is the scene in which Abraham Lincoln signs the call for the first 75,000 volunteers. However, the first aggression in the Civil War, made when the Confederate troops fired on Fort Sumter in 1861, is not mentioned in the film.[134] The film suggested that the Ku Klux Klan restored order to the postwar South, which was depicted as endangered by abolitionists, freedmen, and carpetbagging Republican politicians from the North. This is similar to the Dunning School of historiography which was current in academe at the time.[135] The film is slightly less extreme than the books upon which it is based, in which Dixon misrepresented Reconstruction as a nightmarish time when black men ran amok, storming into weddings to rape white women with impunity.[116]

The film portrayed President Abraham Lincoln as a friend of the South and refers to him as "the Great Heart".[136] The two romances depicted in the film, Phil Stoneman with Margaret Cameron and Ben Cameron with Elsie Stoneman, reflect Griffith's retelling of history. The couples are used as a metaphor, representing the film's broader message of the need for the reconciliation of the North and South to defend white supremacy.[137] Among both couples, there is an attraction that forms before the war, stemming from the friendship between their families. With the war, however, both families are split apart, and their losses culminate in the end of the war with the defense of white supremacy. One of the intertitles clearly sums up the message of unity: "The former enemies of North and South are united again in defense of their Aryan birthright."[138]

The film further reinforced the popular belief held by whites, especially in the South, of Reconstruction as a disaster. In his 1929 book The Tragic Era: The Revolution After Lincoln, Claude Bowers treated The Birth of a Nation as a factually accurate account of Reconstruction.[31]: 432 In The Tragic Era, Bowers presented every black politician in the South as corrupt, portrayed Republican Representative Thaddeus Stevens as a vicious "race traitor" intent upon making blacks the equal of whites, and praised the Klan for "saving civilization" in the South.[31]: 432 Bowers wrote about black empowerment that the worst sort of "scum" from the North like Stevens "inflamed the Negro's egoism and soon the lustful assaults began. Rape was the foul daughter of Reconstruction!"[31]: 432

Academic assessment

[edit]Historian E. Merton Coulter treated The Birth of a Nation as historically correct and painted a vivid picture of "black beasts" running amok, encouraged by alcohol-sodden, corrupt and vengeful black Republican politicians.[31]: 432

Veteran film reviewer Roger Ebert wrote:

... stung by criticisms that the second half of his masterpiece was racist in its glorification of the Ku Klux Klan and its brutal images of blacks, Griffith tried to make amends in Intolerance (1916), which criticized prejudice. And in Broken Blossoms he told perhaps the first interracial love story in the movies—even though, to be sure, it's an idealized love with no touching.[139]

Despite some similarities between the Congressman Stoneman character and Rep. Thaddeus Stevens of Pennsylvania, Rep. Stevens did not have the family members described and did not move to South Carolina during Reconstruction. He died in Washington, D.C. in 1868. However, Stevens's biracial housekeeper, Lydia Hamilton Smith, was considered his common-law wife, and was generously provided for in his will.[140]

In the film, Abraham Lincoln is portrayed in a positive light due to his belief in conciliatory postwar policies toward Southern whites. The president's views are opposite those of Austin Stoneman, a character presented in a negative light, who acts as an antagonist. The assassination of Lincoln marks the transition from war to Reconstruction, each of which periods has one of the two "acts" of the film.[141] In including the assassination, the film also establishes to the audience that the plot of the movie has historical basis.[142] Franklin wrote the film's depiction of Reconstruction as a hellish time when black freedmen ran amok, raping and killing whites with impunity until the Klan stepped in is not supported by the facts. Instead, most freed slaves continued to work for their former masters in Reconstruction for the want of a better alternative and, though relations between freedmen and their former masters were not friendly, very few freedmen sought revenge against the people who had enslaved them.[31]: 427–428

The depictions of mass Klan paramilitary actions did not have historical equivalents. However, there were incidents in 1871 where Klan groups traveled from other areas in fairly large numbers to aid localities in disarming local companies of the all-black portion of the state militia, and the organized Klan continued activities as small groups of "night riders".[143]

The civil rights movement of the 1960s inspired a new generation of historians, such as scholar Eric Foner, who led a reassessment of Reconstruction. Building on W. E. B. DuBois' work, but also adding new sources, they focused on achievements of the African American and white Republican coalitions, such as establishment of universal public education and charitable institutions in the South and extension of voting rights to black men. In response, the Southern-dominated Democratic Party and its affiliated white militias used extensive terrorism, intimidation and even assassinations to suppress African-American leaders and voters in the 1870s and thereby to regain power in the South.[144]

Legacy

[edit]Film innovations

[edit]In his review of The Birth of a Nation in 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die, Jonathan Kline writes that "with countless artistic innovations, Griffith essentially created contemporary film language... virtually every film is beholden to [The Birth of a Nation] in one way, shape or form. Griffith introduced the use of dramatic close-ups, tracking shots, and other expressive camera movements; parallel action sequences, crosscutting, and other editing techniques". He added that "the fact that The Birth of a Nation remains respected and studied to this day—despite its subject matter—reveals its lasting importance."[145]

Griffith helped to pioneer such camera techniques as close-ups, fade-outs, and a carefully staged battle sequence with hundreds of extras made to look like thousands.[9] The Birth of a Nation also contained many new artistic techniques, such as color tinting for dramatic purposes, and featuring its own musical score written for an orchestra.[36]

Home media and restorations

[edit]For many years, The Birth of a Nation was poorly represented in home media and restorations. This stemmed from several factors, one of which was the fact that Griffith and others had frequently reworked the film, leaving no definitive version. According to the silent film website Brenton Film, many home media releases of the film consisted of "poor quality DVDs with different edits, scores, [and] running speeds," which were "usually in definitely unoriginal black and white."[146]

One of the earliest high-quality home versions was film preservationist David Shepard's 1992 transfer of a 16mm print for VHS and LaserDisc release via Image Entertainment. A short documentary, The Making of The Birth of a Nation, newly produced and narrated by Shepard, was also included. Both were released on DVD by Image in 1998 and the United Kingdom's Eureka Entertainment in 2000.[146]

In the UK, Photoplay Productions restored the Museum of Modern Art's 35mm print that was the source of Shepard's 16 mm print, though they also augmented it with extra material from the British Film Institute. It was also given a full orchestral recording of the original Breil score. Though broadcast on Channel 4 television and screened in theaters many times, Photoplay's 1993 version was never released on home video.[146]

Shepard's transfer and documentary were reissued in the US by Kino Video in 2002, this time in a 2-DVD set with added extras on the second disc. These included several Civil War shorts also directed by D. W. Griffith.[146] In 2011, Kino prepared an HD transfer of a 35 mm negative from the Paul Killiam Collection. They added some material from the Library of Congress and gave it a new compilation score. This version was released on Blu-ray by Kino in the US, Eureka in the UK (as part of their "Masters of Cinema" collection) and Divisa Home Video in Spain.[146]

In 2015, the year of the film's centenary, Photoplay Productions' Patrick Stanbury, in conjunction with the British Film Institute, carried out the first full restoration. It mostly used new 4K scans of the LoC's original camera negative, along with other early generation material. It, too, was given the original Breil score and featured the film's original tinting for the first time since its 1915 release. The restoration was released on a 2-Blu-ray set in the UK and US by the BFI and Twilight Time, alongside a host of extras, including many other newly restored Civil War-related films from the period.[146]

In popular culture

[edit]- The Birth of a Nation's reverent depiction of the Klan was lampooned in Mel Brooks's Blazing Saddles (1974).[147]

- Ryan O'Neal's character Leo Harrigan in Peter Bogdanovich's Nickelodeon (1976) attends the premiere of The Birth of a Nation and realizes that it will change the course of American cinema.[148]

- Clips from Griffith's film are shown in

- Robert Zemeckis's Forrest Gump (1994), where the footage is meant to portray the titular character's ancestor and namesake Nathan Bedford Forrest[149]

- The closing montage of Spike Lee's Bamboozled (2000), along with other footage from demeaning portrayals of African Americans in early 20th century film[121]

- Lee's BlacKkKlansman (2018), where Harry Belafonte's character Jerome Turner speaks about its role in the lynching of Jesse Washington as the modern Ku Klux Klan led by Grand Wizard David Duke (Topher Grace) screens it as propaganda.[150]

- Director Kevin Willmott's mockumentary C.S.A.: The Confederate States of America (2004) portrays an imagined history where the Confederacy won the Civil War. It shows part of an imagined Griffith film, The Capture of Dishonest Abe, which resembles The Birth of a Nation and was supposedly adapted from Thomas Dixon's The Yankee.[123]

- In Justin Simien's Dear White People (2014), Sam (Tessa Thompson) screens a short film called The Rebirth of a Nation which portrays white people wearing whiteface while criticizing Barack Obama.[121]

- In 2016, Nate Parker produced and directed the film The Birth of a Nation, based on Nat Turner's slave rebellion; Parker clarified:

I've reclaimed this title and re-purposed it as a tool to challenge racism and white supremacy in America, to inspire a riotous disposition toward any and all injustice in this country (and abroad) and to promote the kind of honest confrontation that will galvanize our society toward healing and sustained systemic change.[151]

- Dinesh D'Souza's 2016 political documentary Hillary's America: The Secret History of the Democratic Party depicts President Wilson and his cabinet viewing The Birth of a Nation in the White House before a Klansman comes out of the screen and into the real world. The film is meant to accuse the Democratic Party and the American political left in covering up its past support of white supremacy and continuing it through welfare policies and machine politics.[152] The title of D'Souza's 2018 film The Death of a Nation is a reference to Griffith's film, and like his previous film is meant to accuse the Democratic Party, and historical American left-wing of racism.[152]

- The 2019 feature film I Am Not a Racist is a comedy that uses The Birth of a Nation's original material, changing its order and creating new contexts and new dialogues to mock the movie and to criticize racism.[153]

- In 2019, Bowling Green State University renamed its Gish Film Theater, which was named for actress Lillian Gish, after protests alleging that using her name is inappropriate because of her role in The Birth of a Nation.[154]

See also

[edit]- List of American films of 1915

- List of films and television shows about the American Civil War

- List of films featuring slavery

- List of highest-grossing films

- List of racism-related films

- Lost Cause of the Confederacy

- Racism against African Americans

- Racism in the United States

- Tom Rice (film historian)

References

[edit]Informational notes

- ^ Runtime depends on projection speed ranging 16 to 24 frames per second

Citations

- ^ "D. W. Griffith: Hollywood Independent". Cobbles.com. June 26, 1917. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ^ "The Birth of a Nation (U)". Western Import Co. Ltd. British Board of Film Classification. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Hall, Sheldon; Neale, Stephen (2010). Epics, spectacles, and blockbusters: a Hollywood history. Contemporary Approaches to Film and Television. Wayne State University Press. p. 270 (note 2.78). ISBN 978-0-8143-3697-7.

In common with most film historians, he estimates that The Birth of Nation cost "just a little more than $100,000" to produce...

- ^ a b Monaco, James (2009). How to Read a Film: Movies, Media, and Beyond. Oxford University Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-19-975579-0.

The Birth of a Nation, costing an unprecedented and, many believed, thoroughly foolhardy $110,000, eventually returned $20 million and more. The actual figure is hard to calculate because the film was distributed on a "states' rights" basis in which licenses to show the film were sold outright. The actual cash generated by The Birth of a Nation may have been as much as $50 million to $100 million, an almost inconceivable amount for such an early film.

- ^ The Birth of a Nation. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved August 1, 2022.

- ^ "The Birth of a Nation (1915)". filmsite.org. Archived from the original on September 3, 2011.

- ^ a b Niderost, Eric (October 2005). "'The Birth of a Nation': When Hollywood Glorified the KKK". HistoryNet. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ Hubbert, Julie (2011). Celluloid Symphonies: Texts and Contexts in Film Music History. University of California Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-520-94743-6.

- ^ a b Norton, Mary Beth (2015). A People and a Nation, Volume II: Since 1865, Brief Edition. Cengage Learning. p. 487. ISBN 978-1-305-14278-7.

- ^ "Souvenir. The Birth of a Nation" (PDF). 1915. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- ^ a b c Slide, Anthony (2004). American Racist: The Life and Films of Thomas Dixon. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2328-8. Retrieved September 16, 2018 – via Project MUSE.

- ^ Rampell, Ed (March 3, 2015). "'The Birth of a Nation': The most racist movie ever made". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 7, 2021.

- ^ "MJ Movie Reviews – Birth of a Nation, The (1915) by Dan DeVore". Archived from the original on July 7, 2009.

- ^ Armstrong, Eric M. (February 26, 2010). "Revered and Reviled: D.W. Griffith's 'The Birth of a Nation'". The Moving Arts Film Journal. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- ^ Stand Your Ground: A History of America's Love Affair with Lethal Self-Defense. Beacon Press. 2017. p. 81.

The Birth of a Nation was an instant success across the nation, grossing more than any prior motion picture ... white audiences throughout the nation enjoyed the romantic depiction of the Old South.

- ^ a b "The Black Activist Who Fought Against D. W. Griffith's "The Birth of a Nation"". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ Sonneborn, Liz (2002). A to Z of American Women in the Performing Arts. New York: Facts on File, Inc. p. 85. ISBN 9780816043989.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ "'The Birth of a Nation' Documents History". The Los Angeles Times. January 4, 1993. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ Griffith followed the then-dominant Dunning School or "Tragic Era" view of Reconstruction presented by early 20th-century historians such as William Archibald Dunning and Claude G. Bowers.Stokes 2007, pp. 190–191.

- ^ "Index of Titles: 1914–15", The Griffith Project, British Film Institute, 2004, doi:10.5040/9781838710729.0007, ISBN 978-1-84457-043-0, retrieved May 8, 2022 – via Google Books

- ^ McKernan, Luke (2018). Charles Urban: Pioneering the Non-Fiction Film in Britain and America, 1897–1925. University of Exeter Press. ISBN 978-0859892964.

- ^ Stokes 2007.

- ^ Usai, P. (2019). The Griffith Project, Volume 8. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781839020155.

- ^ ...(the) portrayal of "Austin Stoneman" (bald, clubfoot; mulatto mistress, etc.) made no mistaking that, of course, Stoneman was Thaddeus Stevens..." Robinson, Cedric J.; Forgeries of Memory and Meaning. University of North Carolina, 2007; p. 99.

- ^ Garsman, Ian (2011–2012). "The Tragic Era Exposed". Reel American History. Lehigh University Digital Library. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved January 23, 2013.

- ^ Corkin, Stanley (1996). Realism and the birth of the modern United States : cinema, literature, and culture. Athens: University of Georgia Press. p. 156. ISBN 0-8203-1730-6. OCLC 31610418.

- ^ a b c d e Stokes 2007

- ^ Leistedt, Samuel J.; Linkowski, Paul (January 2014). "Psychopathy and the Cinema: Fact or Fiction?". Journal of Forensic Sciences. 59 (1): 167–174. doi:10.1111/1556-4029.12359. PMID 24329037. S2CID 14413385.

- ^ a b Rohauer, Raymond (1984). "Postscript". In Crowe, Karen (ed.). Southern horizons : the autobiography of Thomas Dixon. Alexandria, Virginia: IWV Publishing. pp. 321–337. OCLC 11398740.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Franklin, John Hope (Autumn 1979). "The Birth of a Nation: Propaganda as History". Massachusetts Review. 20 (3): 417–434. JSTOR 25088973.

- ^ a b c d e f Dixon, Thomas Jr. (1984). Crowe, Karen (ed.). Southern horizons: the autobiography of Thomas Dixon. Alexandria, Virginia: IWV Publishing. OCLC 11398740.

- ^ Lynskey, Dorian (March 31, 2015). "Still lying about history". Slate. Retrieved February 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Crowe, Karen (1984). "Preface". In Crowe, Karen (ed.). Southern horizons : the autobiography of Thomas Dixon. Alexandria, Virginia: IWV Publishing. pp. xv–xxxiv. OCLC 11398740.

- ^ Merritt, Russell (Autumn 1972). "Dixon, Griffith, and the Southern Legend". Cinema Journal. 12 (1): 26–45. doi:10.2307/1225402. JSTOR 1225402.

- ^ a b c Stokes, Melvyn (2007). D.W. Griffith's the Birth of a Nation: A History of "the Most Controversial Motion Picture of All Time". Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 105, 122, 124, 178. ISBN 978-0-19-533678-8.

- ^ a b c Eagan, Daniel (2010). America's film legacy: the authoritative guide to the landmark movies in the National Film Registry. National Film Preservation Board (U.S.). New York: Continuum. pp. 42–44. ISBN 9781441116475. OCLC 676697377.

- ^ Stokes 2007, p. 93.

- ^ Seelye, Katharine Q. (June 10, 2002). "When Hollywood's Big Guns Come Right From the Source". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 7, 2024. Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ Cal Parks, Griffith Ranch

- ^ a b 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Hickman 2006, p. 77

- ^ Hickman 2006, pp. 68–69.

- ^ a b Hickman 2006, p. 78

- ^ a b Marks, Martin Miller (1997). Music and the Silent Film: Contexts and Case Studies, 1895–1924. Oxford University Press. pp. 127–135. ISBN 978-0-19-536163-6.

- ^ Qureshi, Bilal (September 20, 2018). "The Anthemic Allure Of 'Dixie,' An Enduring Confederate Monument".

- ^ Eder, Bruce. "Birth of a Nation [Original Soundtrack]". AllMusic. All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ Capps, Kriston (May 23, 2017). "Why Remix The Birth of a Nation?". The Atlantic. Retrieved February 28, 2018.

- ^ a b Lennig, Arthur (April 2004). "Myth and Fact: The Reception of The Birth of a Nation". Film History. 16 (2): 117–141. doi:10.2979/FIL.2004.16.2.117. Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved June 16, 2019. Gale Power Search All the online versions are missing the 8 illustrations in the printed version.

- ^ "A Riot". Los Angeles Times. January 12, 1915. p. 24.

- ^ Warnack, Henry Cristeen (February 9, 1915). "Trouble over The Clansman". Los Angeles Times. p. 16.

- ^ Campbell 1981, p. 50.

- ^ "The Birth of a Nation". The New York Times. March 4, 1915.

- ^ Campbell 1981, p. 59.

- ^ Gallagher, Gary W. (2008) Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollywood & Popular Art Shape What We Know About the Civil War Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. p.42. ISBN 978-0-8078-3206-6

- ^ "Fashion's Freaks". Sandusky Register. Sandusky, Ohio. January 2, 1915. p. 5.

- ^ "Blow at Free Speech". Potter Enterprise. Coudersport, Pennsylvania. January 27, 1915. p. 6.

- ^ "'The Clansman' Opens Sunday, Opera House.Costliest Motion Picture Drama Ever Produced". Bakersfield Californian. Bakersfield, California. October 8, 1915. p. 9.

- ^ a b "President to See Movies [sic]". Washington Evening Star. February 18, 1915. p. 1.

- ^ a b c d "Dixon's Play Is Not Indorsed by Wilson". Washington Times. April 30, 1915. p. 6.

- ^ Wade, Wyn Craig (1987). The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0671414764.

- ^ a b c d e f g Benbow, Mark (October 2010). "Birth of a Quotation: Woodrow Wilson and 'Like Writing History with Lightning'". The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era. 9 (4): 509–533. doi:10.1017/S1537781400004242. JSTOR 20799409. S2CID 162913069.

- ^ Wilson, Woodrow (1916). A History of the American People. Vol. 5. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 64.

- ^ Link, Arthur Stanley (1956). Wilson: The New Freedom. Princeton University Press. pp. 253–254.

- ^ Loewen, James W. (2018). Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong (Reprint ed.). The New Press. ISBN 9781620973929.

- ^ McEwan, Paul (2015). The Birth of a Nation. London: Palgrave. pp. 80–81. ISBN 978-1-84457-657-9.

- ^ ""Art [and History] by Lightning Flash": The Birth of a Nation and Black Protest". Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media. Fairfax, Virginia: George Mason University. Archived from the original on September 9, 2015. Retrieved February 13, 2020.

- ^ a b Cook, Raymond A. (1968). Fire from the Flint: The Amazing Careers of Thomas Dixon. Winston-Salem, N.C.: J. F. Blair. OCLC 729785733.

- ^ "'The Birth of a Nation' Shown". The Washington Evening Star. February 20, 1915. p. 12.

- ^ "Chief Justice and Senators at 'Movie'". Washington Herald. February 20, 1915. p. 4.

- ^ "Movies at Press Club". The Washington Post. February 20, 1915. p. 5.

- ^ "Birth of a Nation. Noted Men See Private Exhibition of Great Picture". New York Sun. February 22, 1915. p. 7.

- ^ Wade, Wyn Craig (1987). The Fiery Cross: The Ku Klux Klan in America. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0671654559.

- ^ Leitner, Andrew, Thomas Dixon, Jr.: Conflicts in History and Literature, Documenting the American South, University Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, retrieved May 6, 2019

- ^ Yellin, Eric S. (2013). Racism in the Nation's Service: Government Workers and the Color Line in Woodrow Wilson's America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina. p. 127. ISBN 9781469607207. Archived from the original on February 7, 2018.

- ^ Schickel, Richard (1984). D. W. Griffith: An American Life. New York: Limelight Editions, p. 282.

- ^ This includes the one at the Internet Movie Archive [1] and the Google video copy [2] Archived August 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine and Veoh Watch Videos Online | The Birth of a Nation | Veoh.com Archived June 9, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. However, of multiple YouTube copies, one that has the full opening titles is DW GRIFFITH THE BIRTH OF A NATION PART 1 1915 on YouTube

- ^ Miller, Nicholas Andrew (2002). Modernism, Ireland and the erotics of memory. Cambridge University Press. p. 226. ISBN 978-0-521-81583-3.

- ^ Rushing, S. Kittrell (2007). Memory and myth: the Civil War in fiction and film from Uncle Tom's cabin to Cold mountain. Purdue University Press. p. 307. ISBN 978-1-55753-440-8.

- ^ Corkin, Stanley (1996). Realism and the birth of the modern United States:cinema, literature, and culture. University of Georgia Press. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-0-8203-1730-4.

- ^ a b Ang, Desmond (2023). "The Birth of a Nation: Media and Racial Hate". American Economic Review. 113 (6): 1424–1460. doi:10.1257/aer.20201867. ISSN 0002-8282.

- ^ a b "A Tarnished Silver Screen: How a racist film helped the Ku Klux Klan grow for generations". The Economist. March 27, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Esposito, Elena; Rotesi, Tiziano; Saia, Alessandro; Thoenig, Mathias (2023). "Reconciliation Narratives: The Birth of a Nation after the US Civil War". American Economic Review. 113 (6): 1461–1504. doi:10.1257/aer.20210413. hdl:11585/927713. ISSN 0002-8282. S2CID 155099706.

- ^ Wiggins, David K. (2006). Out of the Shadows: A Biographical History of African American Athletes. University of Arkansas Press. p. 59.

- ^ Stinson Liles (January 28, 2018). "A 1905 Silent Movie Revolutionizes American Film—and Radicalizes American Nationalists". Southern Hollows podcast (Podcast). Retrieved June 3, 2018.

- ^ Gallen, Ira H. & Stern Seymour. D.W. Griffith's 100th Anniversary The Birth of a Nation (2014) pp. 47f.

- ^ Gaines, Jane M. (2001). Fire and Desire: Mixed-Race Movies in the Silent Era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 334.

- ^ Christensen, Terry (1987). Reel Politics, American Political Movies from Birth of a Nation to Platoon. New York: Basil Blackwell Inc. pp. 19. ISBN 978-0-631-15844-8.

- ^ McEwan, Paul (2015). The Birth of a Nation. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-844-57659-3. Retrieved June 24, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Film Reviews: The Birth of a Nation". Variety. March 1, 1915. p. 23. Retrieved August 11, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Gallagher, Gary W. (2008) Causes Won, Lost, and Forgotten: How Hollywood & Popular Art Shape What We Know About the Civil War Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press. p.45. ISBN 978-0-8078-3206-6

- ^ Aberdeen, J. A. "Distribution: States Rights or Road Show". Hollywood Renegades Archive. Archived from the original on March 20, 2015. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ Doherty, Thomas (February 8, 2015). "'The Birth of a Nation' at 100: "Important, Innovative and Despicable" (Guest Column)". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 9, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- ^ a b c Schickel, Richard (1984). D.W. Griffith: An American Life. Simon and Schuster. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-671-22596-4. Archived from the original on January 6, 2017.

- ^ a b Wasko, Janet (1986). "D.W. Griffiths and the banks: a case study in film financing". In Kerr, Paul (ed.). The Hollywood Film Industry: A Reader. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-7100-9730-9.